To Tao all under heaven will come as streams and torrents flow into a great river or sea.— Tao te ching 32 (Waley)

Say: All things are of God.— Bahá'u'lláh, Book of the Covenant

All persons, living and dead, are purely coincidental.— Kurt Vonnegut, Timequake

(from each equinoxious points of view, the one fellow's fetch being the other follow's person)[next]— Finnegans Wake, 85

No man is good enough to govern another without that other's consent.No consent or consensus based on denial or distrust is good enough to govern a community. [next]— Abraham Lincoln

all the animals and fowls that were the people ran here and there, for each one seemed to have his own little vision that he followed and his own rules; and all over the universe I could hear the winds at war like wild beasts fighting.Meanwhile the sacred tree at the center of the nation's hoop had disappeared from the vision. [next]— Neihardt 1932, 29

The earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens.— Bahá'u'lláh, Tablet of Maqṣúd

The well-being of mankind, its peace and security, are unattainable unless and until its unity is firmly established.

What bird has done yesterday man may do next year, be it fly, be it moult, be it hatch, be it agreement in the nest.[next]— Finnegans Wake, 112

The circumstance that each person is a locus in a network of relations implies that selfishness is self-defeating. On the other hand, too much conformity to customary patterns of belief and behavior, disregarding the actual circumstances of the time, can defeat (or at least anesthetize) the community guided by those beliefs.

[next]

Consider this remark by Edmund Burke (‘Preface to Brissot's Address’, 1794):

Whoever undertakes to set himself up as a judge of Truth and Knowledge is shipwrecked by the laughter of the gods.

If the divine sense of humor has such a lethal edge, maybe it would be better for us humans to laugh at ourselves, and let the gods look elsewhere for amusement. Certainly we have lots to laugh at. Even Burke, if we take him as claiming to know what the gods laugh at, is recklessly risking his own wreck.

By the way, this quotation is often attributed to Albert Einstein; indeed i first came across it as Einstein's and didn't discover its real source until, in the process of researching this book, i searched for the specific source of it. I also discovered that the story in Chapter 8 about Mark Twain as a cub reporter may be apocryphal: it's widely replicated around the Internet, but i've found no reference to it which gives an original source in Twain's works (or anyone else's). But perhaps these are just examples of the way that stories and proverbs work their way into the ‘common stock of knowledge’, leaving the original creator's intentions behind as they take on meaning for other users.

[next]

Learning is a natural process of pursuing personally meaningful goals, and it is active, volitional, and internally mediated; it is a process of discovering and constructing meaning from information and experience, filtered through the learner's unique perceptions, thoughts, and feelings.When we consider learning as a constructive process, we think of experience and information as the material inputs to the process. But the other side of the learning coin is a process of integrated differentiation, like the development of a bodymind from a single cell. In this process we learn by making distinctions within the phaneron; and the “bits” of information which appear as inputs to a construction process are really products of the analysis which we do in order to describe the process of interbeing. [next]— American Psychological Association, 1993 (in McCombs and Whisler 1997, 5)

Recognition of others as experiencing subjects is essential to the nature of the human animal (and probably other social mammals as well: see for instance de Waal 1996, chapter 2). Michael Tomasello (1999) found the uniquely human way of life to be based on our ability to identify with other selves: through ‘joint attention’ you understand that other people use things to realize goals just as you do. He offered this account of what happens when humans deal with artifacts such as texts:

An individual confronts an artifact or cultural practice that she has inherited from others, along with a novel situation for which the artifact does not seem fully suited. She then assesses the way the artifact is intended to work (the intentionality of the inventor), relates this to the current situation, and then makes a modification to the artifact. In this case the collaboration is not actual, in the sense that two or more individuals are simultaneously present and collaborating, but rather virtual in the sense that it takes place across historical time as the current individual imagines the function the artifact was intended to fulfill by previous users, and how it must be modified to meet the current problem situation.The act of imagining ‘the function the artifact was intended to fulfill’ need not be self-conscious – in fact it is often no more conscious than the act of constructing a sentence in conversation. Semiotically, the ‘modification’ is an interpretant of the artifact considered as a sign. In order to carry cultural traditions forward in this way, the subject must be conscious of the situation in a (perhaps) uniquely human way, but not necessarily meta-conscious of her acts as such. In some cases of ‘sociogenesis’, as Tomasello calls it, the collaboration is not virtual but actual, with two or more individuals interacting in “real time.” This is in fact the prototypical situation; virtual collaboration does not develop at all if a child is deprived of real-time collaboration with caregivers.— Tomasello (1999, 41)

This is the essence of the human dialogue which generates cultures and persons. Our collaborative practices of guided and guiding interaction with each other, both actual and artifactual (virtual), weave the network of connections that we call a community or a culture.

[next]

On a purely perceptual level, the brain does the same thing when it ‘fills in’ the blind spot which is due to the structure of the retina. There is no blank area in your visual field, even when you close one eye. Likewise we unconsciously fill in the gaps in the cognitive bubbles we have constructed, individually and collectively, unless some kind of surprise wakes us up to them.

To the non-participating observer, it is clear that the construction and maintenance of consensus requires a lot of semiotic work “behind the scenes.” But an established social order tends to rely on unquestioned and unquestionable authority as a short cut through, or substitute for, the hard work of consensus-building. An authority figure offers an anchor or a secure foundation when the world threatens to slide into chaos.

Human beings, fearing their own transience, have always associated value with permanence and preferred to put their trust in those who were ready to claim an unchanging truth.But the value attached to permanence is ever at odds with the value attached to life and learning, for these are dynamic and transitory. [next]— M.C. Bateson (2000, 135)

The power of ‘joint contruals’, when they overcome differences to achieve unity of purpose, is celebrated in Thomas 48 (Meyer):

Jesus said, ‘If two make peace with each other in a single house, they will say to the mountain, “Move from here,” and it will move.’Here conflict resolution appears as “magical” in its effects as ‘faith’ is said to be in other gospels (Matthew 17:20, 21:21; Mark 11:23; Luke 17:6). In the Anthropocene, ‘joint projects’ (especially when powered by fossil fuels) have quite literally moved mountains, and concentrated social power has escalated war between human groups as well as a virtual war against nature. Modern empire-building and colonization have arguably done more harm than good. Even the social project of education has had mixed results, as Stanilas Dehaene observes:

Through education, we convey to others the best thoughts of the thousands of human generations that preceded us. Every word, every concept we learn is a small conquest that our ancestors passed on to us. Without language, without cultural transmission, without communal education, none of us could have discovered, alone, all the tools that currently extend our physical and mental abilities. Pedagogy and culture make each of us the heir to an extensive chain of human wisdom.[next]But Homo sapiens’ dependency on social communication and education is as much of a curse as it is a gift. On the flip side of the coin, it is education’s fault that religious myths and fake news propagate so easily in human societies. From the earliest age, our brains trustfully absorb the tales we are told, whether they are true or false. In a social context, our brains lower their guard; we stop acting like budding scientists and become mindless lemmings. This can be good—as when we trust the knowledge of our science teachers, and thus avoid having to replicate every experiment since Galileo’s time! But it can also be detrimental, as when we collectively propagate an unreliable piece of “wisdom” inherited from our forebears.— Dehaene 2020, 173-4

Man's destiny on earth, as I am led to conceive it, consists in the realization of a perfect society, fellowship, or brotherhood among men, proceeding upon a complete Divine subjugation in the bosom of the race, first of self-love to brotherly love, and then of both loves to universal love or the love of God, as will amount to a regenerate nature in man, by converting first his merely natural consciousness, which is one of comparative isolation and impotence, into a social consciousness, which is one of comparative omnipresence and omnipotence; and then and thereby exalting his moral freedom, which is a purely negative one, into an aesthetic or positive form: so making spontaneity and not will, delight and no longer obligation, the spring of his activity.Later (p. 10) in the book, he refers to the ‘perfect society, fellowship, or brotherhood among men’ as ‘the Social principle’ – which Peirce identified as the foundation of logic. Peirce also expanded on this theme in ‘Evolutionary Love’ (1893):— Henry James (1863, 6)

… We are to understand, then, that as darkness is merely the defect of light, so hatred and evil are mere imperfect stages of ἀγάπη and ἀγαθόν, love and loveliness. This concords with that utterance reported in John's Gospel: “God sent not the Son into the world to judge the world; but that the world should through him be saved. He that believeth on him is not judged: he that believeth not hath been judged already.… And this is the judgment, that the light is come into the world, and that men loved darkness rather than the light.” That is to say, God visits no punishment on them; they punish themselves, by their natural affinity for the defective. Thus, the love that God is, is not a love of which hatred is the contrary; otherwise Satan would be a coordinate power; but it is a love which embraces hatred as an imperfect stage of it, an Anteros—yea, even needs hatred and hatefulness as its object. For self-love is no love; so if God's self is love, that which he loves must be defect of love; just as a luminary can light up only that which otherwise would be dark. Henry James, the Swedenborgian, says: “It is no doubt very tolerable finite or creaturely love to love one's own in another, to love another for his conformity to oneself: but nothing can be in more flagrant contrast with the creative Love, all whose tenderness ex vi termini must be reserved only for what intrinsically is most bitterly hostile and negative to itself.” This is from Substance and Shadow: an Essay on the Physics of Creation.In the century and a half since these reflections on ‘the Social principle,’ we have seen more of the dark side of the ‘groupish components of human moral behavior’ (Wrangham 2019, 199). Groupishess often amounts to a collective selfishness which tends to increase hostility between human groups rather than leading to universal love. Meanwhile the concentration of power in oligarchies and corporate systems has proven destructive to the more-than-human world as well as human nature and morality itself.— EP1:353-4, W8:184-5, 1893

The globalized economy which emerged in the latter half of the 20th Century could be considered a unifying force from the human point of view, but it has already exceeded planetary boundaries (Rockström and Gaffney 2021), and the superorganism seems unable to give up growing. As the human population grows, the ‘regenerate nature in man’ envisioned by Henry James the elder seems further away than ever. As the planet heats up, and soils and societies degrade, regenerative agriculture and its social equivalents may be the only hope for humanity's future. Will Homo sapiens ever develop a spontaneous (rather than obligatory) love for the whole of nature and ‘the Physics of Creation’? Including its dark side and its “defects”? Who knows? Maybe all we can do now is to “cultivate” and encourage something like that ‘creative Love’ in ourselves and our communities.

[next]

In reality, every fact is a relation. Thus, that an object is blue consists of the peculiar regular action of that object on human eyes. This is what should be understood by the ‘relativity of knowledge.’In his Cambridge Lectures of 1898 (RLT), Peirce explained to an audience of non-logicians how he had developed De Morgan's relational algebra into the logic of relatives which led to his Existential Graphs (which in turn provided the diagrammatic basis for most of his later work on logic as semiotic).CP 3.416 (1892)

The great difference between the logic of relatives and ordinary logic is that the former regards the form of relation in all its generality and in its different possible species while the latter is tied down to the matter of the single special relation of similarity. The result is that every doctrine and conception of logic is wonderfully generalized, enriched, beautified, and completed in the logic of relatives.[next]Thus, the ordinary logic has a great deal to say about genera and species, or in our nineteenth century dialect, about classes. Now, a class is a set of objects comprising all that stand to one another in a special relation of similarity. But where ordinary logic talks of classes, the logic of relatives talks of systems. A system is a set of objects comprising all that stand to one another in a group of connected relations. Induction according to ordinary logic rises from the contemplation of a sample of a class to that of the whole class; but according to the logic of relatives it rises from the contemplation of a fragment of a system to the envisagement of the complete system.CP 4.5 (1898)

Science consists in actually drawing the bow upon truth with intentness in the eye, with energy in the arm.The more the bow is bent, the straighter the flight of the arrow. [next]— Peirce, CP 1.235 (1902)

Truths can be expressed only with symbols – and our ability to use symbolic language gives us the ability to lie. ‘A symbol is defined’ (by Charles Peirce) ‘as a sign which is fit to serve as such simply because it will be so interpreted’: it is supposed (to be intended) to inform somebody (who knows the language well enough to “read” it) about something to which their attention has been directed. But since our actual reading of any linguistic symbol is crucially governed by our language-using habits, symbols are ‘particularly remote from the Truth itself’ (Peirce, EP2:307). Our habits often include attachments or loyalties to stories and other intersubjective realities: these are pragmatically real because they inspire or motivate us to act in ways that make a difference to the real world (whether they are factually grounded or not). They have the power to inform our behavior because, in energetic terms, they have the empower of shared information.

When we recognize patterns in nature well enough to anticipate (with some degree of accuracy) what will happen in a given situation, we are tuned in to the habits of nature itself – of which human habits are a small and subordinate part, crucial as they are for us and our world. Our most systematic way of sharing common beliefs about natural patterns is the communal quest we call science. But scientific method is just a more rigorous and public version of our common-sense way of learning, and critically assessing, our own beliefs about the world.

[next]

To make the reflection that many of the things which appear certain to us are probably false, and that there is not one which may not be among the errors, is very sensible. But to make believe one does not believe anything is an idle and self-deceptive pretence. Of the things which seem to us clearly true, probably the majority are approximations to the truth. We never can attain absolute certainty; but such clearness and evidence as a truth can acquire will consist in its appearing to form an integral unbroken part of the great body of truth. If we could reduce ourselves to a single belief, or to only two or three, those few would not appear reasonable or clear.— Peirce, CP 4.71 (1893)

Much of our ordinary consensus may be confabulated, embodied in fables which, like our intentions, are sustainable insofar as they are not in open conflict with reality. But until we reach the end of the world of experience, the evidence for or against any particular belief is incomplete. We can never be sure that it is true, or that the cognitive bubble – the appearance of ‘the great body of truth’ – will maintain its integrity. The dynamic tension between the complexity of reality and the cognitive drive to simplify our “handle” on it is, like the dance of Shiva, both creative and destructive.

For the inquirer, every new belief begins as a hypothesis, a guess which we hope could be consistent with both the old belief system and the observed facts. When we consider a new hypothesis, we're better off knowing that it's false than relying on it provisionally (which is the nearest we can get to knowing that it is simply true). The honest inquirer therefore is eager to falsify any hypothesis that can be falsified, especially one she is partial to.

A hypothesis is something which looks as if it might be true and were true, and which is capable of verification or refutation by comparison with facts. The best hypothesis, in the sense of the one most recommending itself to the inquirer, is the one which can be the most readily refuted if it is false. This far outweighs the trifling merit of being likely. For after all, what is a likely hypothesis? It is one which falls in with our preconceived ideas. But these may be wrong. Their errors are just what the scientific man is out gunning for more particularly. But if a hypothesis can quickly and easily be cleared away so as to go toward leaving the field free for the main struggle, this is an immense advantage.[next]— Peirce, CP 1.120 (c. 1896)

In sciences in which men come to agreement, when a theory has been broached, it is considered to be on probation until this agreement is reached. After it is reached, the question of certainty becomes an idle one, because there is no one left who doubts it. We individually cannot reasonably hope to attain the ultimate philosophy which we pursue; we can only seek it, therefore, for the community of philosophers. Hence, if disciplined and candid minds carefully examine a theory and refuse to accept it, this ought to create doubts in the mind of the author of the theory himself.— Peirce, EP1:29

Scientific findings are not accepted because somebody says “This is acceptable,” much less because somebody says “I accept this,” regardless of who says it on what occasion or from what office. They are just accepted or not, and the only way we can tell if they are accepted is by finding out whether or not they actually function in the relevant intellectual community as premises or presuppositions used in further inquiry.[next]— Joseph Ransdell, ‘Peirce and The Socratic Tradition’ (cspeirce.com/menu/library/aboutcsp/ransdell/Socratic.htm, accessed 1 June 2011)

These two modes are like the two parts of a cyclic process such as breathing, which alternates between inbreath and outbreath; in practice we step back and forth between them. But Thirdness, or ‘thought’, involves both Secondness and Firstness. When practice and perception are united in the single process of semiosis or meaning, we are immersed in the sense of flow, of humble participation in a systemic process which includes us in itself with all the others. In this humility no one “stands out,” all beings practice together.

All of us on planet Earth are immersed in the biosphere, which is itself immersed in the whole of nature. But we are not aware of this in detached observation, which is essential to science – even to all reasoning, as Peirce/Baldwin said. Is this ‘detachment’ the same as the ‘objectivity’ proper to scientific method? Can you investigate something without having any “vested interest” in the matter? without being motivated by any kind of self-interest? Can you engage in Pure Play with ‘scientific singleness of heart,’ as Peirce called it, without being attached to any particular result or value judgment? Can you explain the difference between practicing science religiously and religious or spiritual detachment?

The scientific method often involves isolating phenomena from the rest of the world, for the sake of simplifying observations and making them relevant to simplified models of nature. To investigate our own immersion in nature we need a science humble enough to include both participation and observation detached from any sense of personal power or privilege.

[next]

Internet activist Eli Pariser coined the term “filter bubble” to refer to selective information acquisition by Web site algorithms (in search-engines, news feeds, flash messages, tweets, RSS, etc.), personalizing search results for users based on past search history, click behavior and location, and “like”-culture, and accordingly filtering away information in conflict with user interest, viewpoint or opinion.In the 21st Century, as the authors of Infostorms explain, filter bubbles became important causes of social polarization, as they tend to ‘isolate users in their cultural, political, ideological, or religious bubbles.’— Hendricks and Hansen 2016, 210

Filter bubbles may stimulate individual narrow-mindedness but are also potentially harmful to the general society, undermining informed civic or public deliberation, debate and discourse and making citizens ever more susceptible to propaganda and manipulation: “A world constructed from the familiar is a world in which there’s nothing to learn … (since there is) invisible autopropaganda, indoctrinating us with our own ideas” (Pariser 2011 , The Economist , June 30)— Hendricks and Hansen 2016, 210

‘Let us not concur casually about the most important matters,’ said Heraclitus (Kahn XI, D. 47).

‘The first thing that the Will to Learn supposes is a dissatisfaction with one's present state of opinion,’ said Peirce (EP2:47, RLT 171). (Dissatisfaction with someone else's present state of opinion, on the other hand, is not conducive to learning unless it leads to genuine dialogue.)

A pragmatist won't be satisfied with her opinion until she thinks through its implications for future practice, which depend on how it works within the meaning space in which it lives. Merleau-Ponty was pragmatist enough to think things through in this way before expressing them in public dialogue.

Each time I find something worth saying, it is because I have not been satisfied to coincide with my feeling, because I have succeeded in studying it as a way of behaving, as a modification of my relations with others and with the world, because I have managed to think about it as I would think about the behavior of another person whom I happened to witness.Anything worth saying is informative insofar as its dialogic involves all three ‘persons’ (first, second and third). If it doesn't imply a modification of our/their relations with one another and the world they have in common, it's hardly worth saying (seriously!). [next]— Merleau-Ponty (1948, 52)

We translate το φρονέειν here as ‘Thought’ (rather than “thinking”) in order to denote a universal (‘divine’) process in which all things are involved, rather than a psychological process that is supposed to happen inside of individual thinkers. This is consistent not only with other fragments of Heraclitus, but also with Peirce's view ‘that our thinking only apprehends and does not create thought, and that that thought may and does as much govern outward things as it does our thinking’ (CP 1.27, 1909). Thoughts, he added, are ‘the objects which thinking enables us to know.’ In another context, he related this to scientific thinking as a communal activity:Speaking with understanding they must hold fast to what is common to all, as a city holds to its law, and even more firmly. For all human laws are nourished by a divine one, which prevails as it will, suffices for all and surpasses them.

Common to all is Thought (ξυνόν ἐστι πᾶσι το φρονέειν).

— Heraclitus, DK 44, 113-14; Kahn LXV, XXX-XXXI.

There is no reason why ‘thought’ … should be taken in that narrow sense in which silence and darkness are favorable to thought. It should rather be understood as covering all rational life, so that an experiment shall be an operation of thought. Of course, that ultimate state of habit to which the action of self-control ultimately tends, where no room is left for further self-control, is, in the case of thought, the state of fixed belief, or perfect knowledge.The ‘circle of society’ is ‘of higher rank’ in this respect: that ‘all the greatest achievements of mind have been beyond the powers of unaided individuals’ (EP1:369). But in another respect, this ‘loosely compacted person’ depends on individual organisms for access to experience – its ‘only teacher’ – just as a biological population or species depends on the survival and reproduction of individuals in order to continue and evolve.Two things here are all-important to assure oneself of and to remember. The first is that a person is not absolutely an individual. His thoughts are what he is ‘saying to himself,’ that is, is saying to that other self that is just coming into life in the flow of time. When one reasons, it is that critical self that one is trying to persuade; and all thought whatsoever is a sign, and is mostly of the nature of language. The second thing to remember is that the man's circle of society (however widely or narrowly this phrase may be understood), is a sort of loosely compacted person, in some respects of higher rank than the person of an individual organism.— Peirce, EP2:337-8, CP 5.420-1

Learning from experience requires contact with the reality which ‘prevails as it will’ regardless of communal consensus as well as individual belief. Yet the system which makes inquiry possible is made of the connections which constitute the community. The individual who devotes himself to inquiry can do so with integrity only by working both with and against the conventions of the society which he inhabits; and insofar as that society is healthy and evolving, it embodies a diversity of habits, just as an ecosystem does.

[next]

Unquestionably, highly complex environments belong to the conditions of possibility for forming communication systems. Above all, two opposing presuppositions must be secured. On the one hand, the world must be densely enough structured so that constructing matching interpretations about the things in it is not pure chance; communication must be able to grasp something (even if one can never know what it ultimately is) that does not permit itself to be decomposed randomly or shifted in itself. On the other, there must be different observations, different situations that constantly reproduce dissimilar perspectives and incongruent knowledges on precisely the same grounds. Correspondingly, one can conceive of communication neither as a system-integrating performance nor as the production of consensus. Either would imply that communication undermines its own presuppositions and that it can be kept alive only by sufficient failure. But what, if not consensus, is the result of communication?The result, according to Luhmann, is to make the system more sensitive to ‘chance, disturbances, and “noise” of all kinds.’ Communication ‘can force disturbances into the form of meaning and thus handle them further.… By communication, the system establishes and augments its sensitivity, and thus it exposes itself to evolution by lasting sensitivity and irritability’ (172).— Niklas Luhmann (1995, 171-2)

Communication then presents challenges to the integrity of the social system – challenges which open its collective cognitive bubble to chaos and thus enable it to grow by incorporating something from outside. The system informs itself by turning “noise” into signal, enabling it to modify its own habits. But the whole process depends on representation of ‘dissimilar perspectives’ on the same object of attention.

[next]

We also hope that the answers to those questions will be consistent with one another, so that the belief system would be a perfect whole if the investigation could ever be completed. The Truth would then be the cognitive bubble that would never be broken from the outside.

The ‘absolutely’ true, meaning what no farther experience will ever alter, is that ideal vanishing-point towards which we imagine that all our temporary truths will some day converge.Peirce's remark about the ‘cheerful hope’ which animates investigators is the 1893 revision of a sentence in ‘How to Make our Ideas Clear’ (1878). The earlier version had said that ‘all the followers of science are fully persuaded that the processes of investigation, if only pushed far enough, will give one certain solution to every question to which they can be applied’ (EP1:138, W3:273). The replacement of a ‘fully persuaded’ conviction by a ‘cheerful hope’ reflects both the maturing of Peirce's fallibilism, and his insistence that optimism is healthy, even when we have no reason to believe that we will ever arrive at complete knowledge or ‘one certain solution to each question.’ This ‘hope’ or ‘persuasion’ is an essential part of the guidance system we call science, not a testable prediction.— William James (1907, 583)

In the view from the 21st Century, Peirce's ‘cheerful hope’ recalls a 19th-Century notion of “progress” which has become as unsustainable as the excesses of the Anthropocene. Or else it is a kind of ‘controlled folly’.

If someone says that he knows something, it must be something that, by general consent, he is in a position to know.No sentient being will ever be in a position to know the Whole Truth which would accurately represent ‘the all of reality’. Is the human community of 2020, with all the “information” deposited in its databanks and shared in its networks, any better informed than it was ten thousand years ago? Is the community of inquiry ‘converging’ on some eternal truth? Symbols grow, but they also decay, like every living system. Is human civilization really progressing, or advancing, or is it degenerating, or collapsing? Or is life on Earth a zero-sum game, relative gains for one system entangled with losses for another? Is anyone in a position to know what lies before us, or after us? We can always hope.— Wittgenstein (1969, #555)

Lo, improving ages wait ye! In the orchard of the bones. Some time very presently now when yon clouds are dissipated after their forty years' shower, the odds are, we shall all be hooked and happy, communionistically, among the fieldnights elycean, élite of the elect, in the land of lost of time.[next]— FW2, 352

the life devoted to the pursuit of truth according to the best known methods on the part of a group of men who understand one another's ideas and works as no outsider can. It is not what they have already found out which makes their business a science; it is that they are pursuing a branch of truth according, I will not say, to the best methods, but according to the best methods that are known at the time. I do not call the solitary studies of a single man a science. It is only when a group of men, more or less in intercommunication, are aiding and stimulating one another by their understanding of a particular group of studies as outsiders cannot understand them, that I call their life a science. It is not necessary that they should all be at work upon the same problem, or that all should be fully acquainted with all that it is needful for another of them to know; but their studies must be so closely allied that any one of them could take up the problem of any other after some months of special preparation and that each should understand pretty minutely what it is that each one's or the others' work consists in; so that any two of them meeting together shall be thoroughly conversant with each others' ideas and the language he talks and should feel each other to be brethren.MS 1334, 11-14

Thomas Kuhn (1969, 210) likewise says that ‘scientific knowledge, like language, is intrinsically the common property of a group or else nothing at all.’ Peirce emphasizes the esoteric side of such specialized inquiry: people outside the group are neither willing nor able to give that kind of attention to it. Yet we have no pragmatic choice but to believe that the objects of that attention are in the public domain, observable by anyone equipped to do so. They all belong to Nature, which includes and determines the characteristics of “human nature.” But it also includes polyversity at every level of semiosis, including perception, as Kuhn explains:

If two people stand at the same place and gaze in the same direction, we must, under pain of solipsism, conclude that they receive closely similar stimuli. (If both could put their eyes at the same place, the stimuli would be identical.) But people do not see stimuli; our knowledge of them is highly theoretical and abstract. Instead they have sensations, and we are under no compulsion to suppose that the sensations of our two viewers are the same. (Sceptics might remember that color blindness was nowhere noticed until John Dalton's description of it in 1794.) On the contrary, much neural processing takes place between the receipt of a stimulus and the awareness of a sensation. Among the few things that we know about it with assurance are: that very different stimuli can produce the same sensations; that the same stimulus can produce very different sensations; and, finally, that the route from stimulus to sensation is in part conditioned by education. Individuals raised in different societies behave on some occasions as though they saw different things. If we were not tempted to identify stimuli one-to-one with sensations, we might recognize that they actually do so.Notice now that two groups, the members of which have systematically different sensations on receipt of the same stimuli, do in some sense live in different worlds. We posit the existence of stimuli to explain our perceptions of the world, and we posit their immutability to avoid both individual and social solipsism.— Kuhn 1969, 192-3

According to Dogen, the study of the Buddha-way is a group inquiry much like a science as described above by Peirce. In an early talk given for his fellow monks, he put it this way:

Although the color of the flowers is beautiful, they do not bloom of themselves; they need the spring breeze to open.[next]The conditions for the study of the Way are also like this; although the Way is complete in everyone, the realization of the Way depends upon collective conditions. Although individuals may be clever, the practice of the Way is done by means of collective power. Therefore, now you should make your minds as one, set your aspirations in one direction, and study thoroughly, seek and inquire.— Dogen, Shobogenzo-zuimonki (Cleary 1980, 794)

… the world is richer than it is possible to express in any single language. Music is not exhausted by its successive stylization from Bach to Schoenberg. Similarly, we cannot condense into a single description the various aspects of our experience. We must call upon numerous descriptions, irreducible one to the other, but connected to each other by precise rules of translation (technically called transformations).[next]— Prigogine, From Being to Becoming, 51

Let us swop hats and excheck a few strong verbs weak oach eather yapyazzard abast the blooty creeks.Thus begins the conversation between Mutt and Jute in the early pages of Finnegans Wake. It continues rather like a dialogue of the deaf:— FW 16

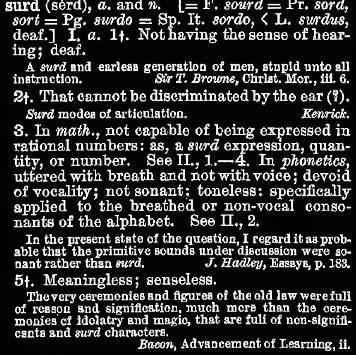

Jute.— Yutah!That last word is not often heard in everyday English, but it suits the story here, as the primal meaning of its Latin root surdus is “deaf.” But then the notion of “hard of hearing” slips over (by way of stuttering, stammering and muttering) into “hard to hear,” and thence to “unintelligible” or “irrational,” and thence to “meaningless.” This diversity was documented by C.S. Peirce in the Century Dictionary:

Mutt.— Mukk's pleasurad.

Jute.— Are you jeff?

Mutt.— Somehards.

Jute.— But you are not jeffmute?

Mutt.— Noho. Only an utterer.

Jute.— Whoa? Whoat is the mutter with you?

Mutt.— I became a stun a stummer.

Jute.— What a hauhauhauhaudibble thing, to be cause! How, Mutt?

Mutt.— Aput the buttle, surd.

In his later work on logic as ‘the Basis of Pragmatism,’ Peirce used the word as a technical term applied to ‘the relation implied in duality,’ which ‘is essentially and purely a dyadic relation’ (EP2:382). A surd relation is the opposite of a dicible one. In less Latinate diction, you could say that a surd relation is “unsayable,” or perhaps “unreasonable.” It can be experienced but not really described.

For the only kind of relation which could be veritably described to a person who had no experience of it is a relation of reason. A relation of reason is not purely dyadic: it is a relation through a sign: that is why it is dicible. Consequently the relation involved in duality is not dicible, but surd …Since all reasoning is in signs, a ‘relation of reason’ is triadic. It lacks the surdity of a ‘purely dyadic relation.’ But the only way Mutt and Jute could enter into a purely dyadic relation would be to collide with each other, perhaps by butting heads. The duality of their duel is clear enough ‘aput the buttle,’ but they do manage to swop hats and excheck a few verbs, thus making their relationship more triadic. If they both sound a bit “stunned,” maybe that's just the effect of taking turns at the buttle.EP2:382-3

Turning to genuine triadic relations, and thus to signs, we find that the Secondness of the dynamic relation between Sign and Object – or in communication, the duality between Utterer and Interpreter – must also be genuine, must be a ‘real’ relation, not a ‘relation of reason.’ As explained elsewhere, the element of Secondness or surdity must be involved in any honest attempt to understand, speak or hear the truth.

This may sound unsound or even absurd, but it is borne out by the twisted history of words themselves. If our language were entirely rational, for instance, the word absurd would mean “far from surd,” just as abnormal means “far from normal.” But in fact surd and absurd mean pretty much the same thing. Why? It's hard to say, surd.

As Peirce remarked in the Century Dictionary, absurd is ‘a word of disputed origin’ – there is no dispute about what it actually means in everyday discourse, but a reasonable account of how it came to mean that has to choose between two possible significations of the prefix ab-. If it means “away from” (as in “absent” or “abnormal”), then combining it with the Latin root surd could not generate the usual meaning of absurd. Some say that the -surd part might come from a Sanskrit root that sounds similar but means “sound” (rather than “deaf”). Then absurd could have meant something like “inharmonious,” and thence “unsound” in the sense of “unreasonable.” The other side in the dispute say that the Latin and English surd is the root, but the prefix ab- acts as an ‘intensive’ rather than a negative (as it seems to do in “aboriginal”), thus making absurdity even more unreasonable or nonsensical than surdity.

Whether we can explain it or not, the common sense of the word absurd is “contrary to common sense” (CD), because that is how people actually use it. Likewise dicible facts, no matter how well known, always carry a residue of unspeakable or inexplicable surdity. ‘Facts don't do what I want them to,’ as Byrne and Eno put it. The element of Secondness in them keeps our knowledge real and our quest for Truth honest.

[next]

… though the question of realism and nominalism has its roots in the technicalities of logic, its branches reach about our life. The question whether the genus homo has any existence except as individuals, is the question whether there is anything of any more dignity, worth, and importance than individual happiness, individual aspirations, and individual life. Whether men really have anything in common, so that the community is to be considered as an end in itself, and if so, what the relative value of the two factors is, is the most fundamental practical question in regard to every public institution the constitution of which we have it in our power to influence.Given that the genome of Homo sapiens has evolved through multilevel selection (E.O. Wilson 2012), it seems there will always be some tension between an individual's values and ‘groupish’ values. Also, authoritarian and democratic governance will always be at odds with each other. The complexity of human society in the Anthropocene entails that conflicts between nested social systems will play out at many levels simultaneously. At the basic level, though, we can ask: Are public institutions here to serve the well-being of individual humans, or are people here to serve the community in which they are embedded? Beyond that, are we all here to serve “humanity,” or is our species here to serve a more-than-human cause such as life on this planet? And what purpose/cause does Life Itself serve? These are the deeper questions behind the philosophical debate between nominalism and realism.— Peirce (EP1:105)

Certainly these deeper questions are fundamental when it comes to political institutions. But as Northrop Frye pointed out (Chapter 8), you cannot escape the question by turning from secular politics to religion, for ‘religious bodies do not effectively express any alternative of loyalty to the totalitarian state, because they use the same metaphors of merging and individual subservience.’ States, corporations and religious bodies are the larger-scale systems which seem to “contain” individual humans; but suppose we consider the social evolution of humanity over an expansive time scale while maintaining the spatial scale of the human bodymind. Then we can see each individual human as a version of “humanity” rather than a minute cell in a huge organism. This would seem compatible with the following remarks by Frye, which continue from those already quoted in Chapter 8:

In our day Simone Weil has found the traditional doctrine of the Church as the Body of Christ a major obstacle – not impossibly the major obstacle – to her entering it. She points out that it does not differ enough from other metaphors of integration, such as the class solidarity metaphor of Marxism, and says:[next]Our true dignity is not to be parts-of a body.… It consists in this, that in the state of perfection which is the vocation of each one of us, we no longer live in ourselves, but Christ lives in us; so that through our perfection Christ … becomes in a sense each one of us, as he is completely in each host. The hosts are not a part of his body.I quote this because, whether she is right or wrong, and whatever the theological implications, the issue she raises is a central one in metaphorical vision, or the application of metaphors to human experience. We are born, we said, within a pre-existing social contract out of which we develop what individuality we have, and the interests of that society take priority over the interests of the individual. Many religions, on the other hand, in their origin, attempt to be re-created societies built on the influence of a single individual: Jesus, Buddha, Lao Tzu, Mohammed, or at most a small group. Such teachers signify, by their appearance, that there are individuals to whom a society should be related, rather than the other way around. Within a generation or two, however, this new society has become one more social contract, and the individuals of the new generations are once again subordinated to it.Paul's conception of Jesus as the genuine individuality of the individual, which is what I think Simone Weil is following here, indicates a reformulating of the central Christian metaphor in a way that unites without subordinating, that achieves identity with and identity as on equal terms. The Eucharistic image, which she also refers to, suggests that the crucial event of Good Friday – the death of Christ on the cross – is one with the death of everything else in the past. The swallowed Christ, eaten, divided, and drunk, in the phrase of Eliot's ‘Gerontion,’ is one with the potential individual buried in the tomb of the ego during the Sabbath of time and history, where it is the only thing that rests. When this individual awakens and we pass to resurrection and Easter, the community with which he is identical is no longer a whole of which he is a part, but another aspect of himself, or, in the traditional metonymic language, another person of his substance.— Frye (1982, 100-01)

With the advent of agriculture, ‘high population density led to centralized authority and stratified societies, and a new mode of social organization emerged’ (Morowitz 2002, 168). Christopher Boehm (2012) argues that the earliest human communities were egalitarian, morality being enforced by the group as a whole rather than specialized “police forces.” As they grew bigger, especially after agriculture became established, need arose for central leadership, and it could no longer be controlled by group consensus; so the leadership became the controlling (governing) agency, with or without the consent of the governed. Religious and political groupings were indistinguishable in this respect until very recently. David Sloan Wilson (2002) gives a similar analysis.

Stuart Kauffman traces a similar development in biological terms, in ‘An Emerging Global Civilization,’ the final chapter of his (1995) book At Home in the Universe. Drawing upon work by Brian Goodwin and Gerry Webster, he begins with Kant, who

writing in the late eighteenth century, thought of organisms as autopoietic wholes in which each part existed for and by means of the whole, while the whole existed for and by means of the parts. [Goodwin and Webster] noted that the idea of an organism as an autopoietic whole had been replaced by the idea of the organism as an expression of a ‘central directing agency.’ The famous biologist August Weismann, at the end of the nineteenth century, developed the view that the organism is created by the growth and development of specialized cells, the ‘germ line,’ which contains microscopic molecular structures, a central directing agency, determining growth and development. In turn, Weismann's molecular structures became the chromosomes, became the genetic code, became the ‘developmental program’ controlling ontogeny. … In this trajectory, we have lost an earlier image of cells and organisms as self-creating wholes.— Kauffman (1995, 274)

Thus we have managed to conjure up “central control” both above and below the scale of human bodymind. Some of the “conflict between science and religion” in the twentieth century was really a struggle between partisans of competing control agencies. But these conflicts can only distract us from the real question: Can humanity as a moral (guiding) agency self-organize, replacing subordination with coordination? Or will it take a central agency (religious or political) to unify humanity by imposing a “new world order” upon it?

Wilson (2002) poses a related question. It seems that religions have evolved their current forms by competing with one another and with other social structures. But the next major transition would require them to give up the competition that has made them what they are. Can they do this? In political terms, can a community, nation or corporation open itself to cooperation with other systems instead of trying to prevail over them? Can civilization itself learn to cooperate with the natural world in the age of overshoot? The question comes to a climax in the 21st Century.

… in the depth of social reality each decision brings unexpected consequences, and man responds to these surprises by inventions which transform the problem.Can humanity rehabilitate its relations with other realities, before it is overtaken by the consequences of its own inventions? [next]— Merleau-Ponty, ‘The Crisis of Understanding,’ 1955 (The Primacy of Perception, 205)

The Earth belongs not to us, we belong to the Earth.

For we are fed of its forest, clad in its wood, barqued by its bark and our lecture is its leave.— The Restored Finnegans Wake, 389

This is the Day whereon the earth shall tell out her tidings.— Bahá'u'lláh (Gleanings XVII)

Euro-American humanism has been a story of writers and scholars who were deeply moved and transformed by their immersion in earlier histories and literatures.… Today a new breed of posthumanists is investigating and experiencing the diverse little nations of the planet, coming to appreciate the “primitive,” and finding prehistory to be an ever-expanding field of richness. We get a glimmering of the depth of our ultimately single human root. Wild nature is inextricably in the weave of self and culture.… The dialogue to open next would be among all beings, toward a rhetoric of ecological relationships.— Gary Snyder (1990, 68)

If we can see (as we once saw very well) that our conversation with the planet is reciprocal and mutually creative, then we cannot help but walk carefully in that field of meaning.— David Suzuki (1997, 206)

The Great Work now, as we move into a new millennium, is to carry out the transition from a period of human devastation of the Earth to a period when humans would be present to the planet in a mutually beneficial manner.[next]— Thomas Berry (1999, 3)

- Power is everywhere. We can’t understand nature or human society without investigating the workings of power.

- Our human ability to overwhelm nature and our tendency toward extreme inequality have both evolved in discrete stages. That is, in neither case was evolution a steady process. It’s possible to pinpoint key moments in biological evolution and social evolution when everything changed due to a dramatic power shift.

- There is a fundamental correlation between physical power and social power. Social scientists sometimes tend to downplay this point. But throughout history, dramatic increases in physical power, derived from new technologies and from harnessing new energy sources, have often tended to lead to more vertical social power [which basically means ‘a few people having more wealth than everybody else, or being able to tell lots of other people what to do’].

- Our problems with power result not just from abuse. We’re rightly outraged by abuses of power in the forms of slavery, despotism, corruption, racism, sexism, and so on. But sometimes the accumulation of too much power within a system is problematic regardless of the benign or sinister intent of system managers.

- The “will to power,” about which German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche wrote, is real — but it isn’t everything. We humans have other instincts that counteract our relentless pursuit of power. Efforts to limit power are deeply rooted in nature’s cycles and balancing mechanisms, and have been expressed in countless social movements over many centuries, including movements to curb the power of rulers, to abolish slavery, and to grant women political rights equal to those enjoyed by men.

- The power of beauty has driven biological evolution as surely as has the pursuit of dominance, and the power of inspiring example has shaped human social evolution as much as the quests for wealth and superior weaponry.

— Heinberg 2021, 7-8

Is there such a thing as progress toward a greater connectedness in this exploding universe?

Every day some connections are made, and some are broken.

We can only imagine where it's all going.

[next]

Way-making (dao) gives things their life,‘Efficacy’ (de) is translated as ‘Virtue’ by Feng and English, ‘power’ by Arthur Waley. If we subtract the moral aspect from ‘Virtue’ and the tendency toward domination from ‘power,’ we get something like the ‘profound efficacy’ of Ames and Hall, or perhaps the ‘buddha-nature’ of Zen.

And their particular efficacy (de) is what nurtures them.

Events shape them,

And having a function consummates them.

It is for this reason that all things (wanwu) honor way-making

And esteem efficacy.

As for the honor directed at way-making

And the esteem directed at efficacy,

It is really something that just happens spontaneously (ziran)

Without anyone having ennobled them.

…

Way-making gives things life

Yet does not manage them.

It assists them

Yet makes no claim upon them.

It rears them

Yet does not lord it over them.

It is this that is called profound efficacy.— Daodejing 51 (Ames and Hall)

When you know the ordinary beings in your own mind, you see the buddha-nature in your own mind. If you want to see buddha, just know ordinary beings. It is just because of the ordinary beings that you lose sight of buddha; it is not buddha that loses sight of ordinary beings. If your own nature is enlightened, ordinary being is buddhahood; if your own nature is confused, buddhahood is ordinary being.— Sutra of Hui-neng (Cleary 1998, 78)