From the human side, Farley Mowat communicated with wolves by pissing around his territory. But could he say anything to them about, say, the Andromeda galaxy? As a member of a symbolic species, he could even talk about things and situations that don't exist, and about whether they could or should exist (modality). Whether this actually raises the level of conversation is debatable – but only in symbols.

Is a symbol system a “code”? That depends on how we use the word “code.”

Our highly developed and highly discriminating abilities to think about situations that we are not observing are developments of powers that we share with other animals. But, at the same time, one must not make the mistake of supposing that language is merely a “code” that we use to transcribe thoughts we could perfectly well have without the “code”. This is a mistake, not only because the simplest thought is altered (e.g., rendered far more determinate) by being expressed in language but because language alters the range of experiences we can have. But the fact remains that our power of imagining, remembering, expecting what is not the case here and now is a part of our nature.[next]— Hilary Putnam (1999, 48)

Avoiding simplistic notions of ‘code’ turns out to be important in other contexts as well; but writers who point this out often omit mention of more cogent usages, and thus appear to be rejecting any and all use of the term. For example, Fauconnier and Turner (2002, 360) refer to the

falsity of the general view that conceptual structure is “encoded” by the speaker into a linguistic structure, and that the linguistic structure is “decoded” by the hearer back into a conceptual structure. An expression provides only sparse and efficient prompts for constructing a conceptual structure.

The authors object to calling the ‘constructing’ process a ‘decoding’ process if (or because) it would imply that the actual (felt) meaning of a properly decoded message is the same as the speaker's felt meaning that was coded in the message. But the determination of a meaning, or an interpretant, is not reversible; there is no “decoding” of a sign into the object or the prior sign that determined it; interpreting is another determination process. Yet there has to be some connection between the speaker's experience and the hearer's; to deny this is to deny that communication is possible, which is hardly a useful assumption. Fauconnier and Turner assume that such a connection exists in their very next sentence: ‘The problem, then, is to find the relations between formally integrated linguistic structure on the one hand and conceptually integrated structures built by the speaker or retrieved by the hearer on the other.’ In speaking of conceptual structures ‘retrieved’ by the hearer, the authors clearly imply a link between speaker's meaning and hearer's meaning.

One way of expressing the link is to use a container metaphor: the concept is in some sense taken out of (or retrieved from) the message by the hearer. But we have no way to place experiences or conceptual structures side by side and see how well they match, because neither party in the exchange (nor any third party) has access to those concepts, except through the medium of the expression. This seems to be the point made by Fauconnier and Turner – but it also seems to be the point encapsulated in Bateson's statement that all messages are coded. The objection raised by Fauconnier and Turner is a useful caveat for users of words in the code family, not a valid reason for avoiding those terms altogether.

Edelman and Tononi (2000, pp. 93-94) raise a similar objection to the use of “code” terminology, referring not to linguistic processes but to those of memory “storage” and “retrieval.”

The problem the brain confronts is that signals from the world do not generally represent a coded input. Instead, they are potentially ambiguous, are context-dependent, and are not necessarily adorned by prior judgement of their significance.Again, the point here in saying that input to the brain is generally not coded is essentially the same point Bateson raised by saying that it is coded: namely that actual meaning is constructed by the brain and only mediately determined by ‘input’ from the external world. Edelman and Tononi are objecting to the misconception that such ‘input’ is represented in or by the brain as stored information in such a way that the input could be restored or retrieved from the brain or its processes. And again, they are not denying a connection between what happens in the world and what happens in the brain, only that the former could be reconstructed from the latter, or that anyone could be in a position to judge the accuracy of the “reconstruction.” Yes, the terms code and representation can be misleading – if the reader fails to decode them appropriately! But if we try to avoid all terms which can be misleading, we will soon have to give up all attempts at communication.

Confusion of “code” with cipher also causes problems in discourse about the ‘genetic code.’

In fact, the image of genes ‘coding for’ physical features is often quite misleading. Rather, genes code for possible physical features, in ways that depend heavily on a variety of environmental factors which affect their expression.(Marcus 2004 gives a fuller explanation.) Here the reading of the ‘coded’ message is a recursive process taking place in an environment (the body) which is itself under development. Each gene may specify a chain of amino acids, which then fold into a protein, and so on … but by the time the ‘meaning’ of the genome is fully expressed (decoded), there is generally no way to trace a specific bodily or behavioral feature back to a single gene. And needless to say, none of the coding or decoding involved here is done consciously. [next]— Clark (1997, 93)

In the jargon of autopoiesis theory, there are no instructional interactions: the autonomy of organisms means that one organism cannot transfer structure to another, and operational closure means that structural changes cannot be imported from events external to the organism. (Unless we count lateral gene transfer as a structural change.)

Edelman (2004) likewise rejects an ‘instructional’ model of learning in favor of ‘selectionism,’ ‘the notion that biological systems operate by selection from populations of variants under a variety of constraints’ (2004, 175) – that is, by selecting niches in meaning space. He also rejects ‘computer models of the brain and mind’ which regard ‘signals from the environment’ as carrying ‘input information that is unambiguous’ when noise is filtered out. ‘Such models are instructive in the sense that information from the world is assumed to elicit the formation of appropriate responses based on logical deduction’ (2004, 35). A better model would represent information as a process powered by metabolism, where the response is co-determined by the habit-structure of the organism and the effects of current experience (which brings ‘fresh energy’ to the Peircean ‘perfect sign’).

A parallel line is taken by Goodenough and Deacon (2003, 814) with regard to moral “codes”:

… morality is not something that humans acquire by means of cultural instruction, although, as we discuss later, culture serves to complement the process in important ways. Rather we are led to moral experience and insight.The implication here is that the entire nature/nurture debate which raged through much of the 20th Century was misconceived. On this point the authors quote Aristotle: ‘We have the virtues neither by nor contrary to our nature. We are fitted by our nature to receive them’ (Goodenough and Deacon 2003, 814). But we neither deduce them logically nor ‘receive them’ passively; where teachers are involved, their role is to give us clues or cues which prompt us to discover or construct them, when we are ready to do so. The same applies to the role of instruction in language learning. [next]

Nobody can doubt that we know laws upon which we can base predictions to which actual events still in the womb of the future will conform to a marked extent, if not perfectly. To deny reality to such laws is to quibble about words. Many philosophers say they are ‘mere symbols.’ Take away the word mere, and this is true. They are symbols; and symbols being the only things in the universe that have any importance, the word ‘mere’ is a great impertinence.Peirce does not say that symbols are the only realities – quite the contrary. He says that they alone have importance, which implies significance, or meaning. In science, biophysical reality is their object. In stories, however, the objects of some symbols may be intersubjective realities, and then their importance is their potential to affect the behavior and the habits of the subjects who “follow” or “believe” those stories. [next]— Peirce (EP2:269)

Even a text which has been transparent may lose its transparency if the reader notices an ambiguity in it. Perceiving an ambiguity entails having to make a conscious choice, and thus makes us conscious of the text as coded. If you manage to recover the transparency of the text without losing its ambiguity, the text has gained for you an added dimension of meaning. Thus the “fall” from ambiguity into opacity may be “redeemed” by a deeper, richer transparency.

[next]

The I Ching includes many layers of text, interpretation and commentary, but its basic framework is a system of 64 signs, called hexagrams because they consist of six lines. Each line can be either whole or divided, so the basic ‘alphabet’ of the system is binary; since each “word” is made of six “letters” arranged vertically, the number of possible “words” is 26 = 64. For a more detailed reading, each hexagram can be considered as an pair of trigrams, one above the other, and each line can take on more specific meaning in that context. To consult this oracle is to first pose a question about a given situation, and then determine which of the 64 hexagrams answers the question when applied to the situation. The determination process bypasses conscious control by introducing a random element (or, as some would prefer to say, by allowing divine or cosmic forces to determine the result).

The fact that the sign obtained can be read as relevant to the question (to any well-formed question) implies that the code “carves” the universe of possible situations into 64 types. Since 64 is a very small number of pieces to carve the whole world into, we could refer to them as archetypes. Any of these archetypal situations could be actualized (or replicated, as Peirce might say) in an indefinitely large number of specific instances, and an archetype can be read into almost any situation.

By focusing on one archetype and crossing it with the actual situation indicated by the question, we can derive a pragmatically useful comment on the situation in ordinary (and vague) language, perhaps with some help from the Chinese text of the I Ching and commentaries on it. The advantage of this for the questioner is that it brings a new perspective to the problem that she may not have anticipated, but which is guaranteed relevant by the ubiquity of the 64 archetypal situations. There is no need to posit anything mysterious or supernatural going on here, though it may help the reader of the oracle to take it as a revelation, just as it may help the reader of any text to believe that it communicates the intention of its author.

The same technique of carving up the universe of discourse into a relatively small number of archetypal parts also operates in astrology with its signs of the zodiac, the Tarot deck with its correspondences to the ‘paths’ of the Kabbalistic ‘Tree of Life,’ and so on. In each case, the ability to read highly generic forms into complicated matters – or to lift the archetypal out of the mundane – can induce a feeling of equanimity while simplifying the decision-making process. Of course the results are not testable in the scientific sense, because one's personal intentions are inseparable from the experimental situation. And of course these methods can be abused; but then so can more “scientific” methods.

In this context, let's try a reading of the Heraclitus fragment: ‘the lord whose oracle is at Delphi neither speaks nor conceals, but gives signs.’ For the Delphic oracle to ‘speak’ could mean that it aims to communicate some definite advice to the inquirer using a common language. To ‘conceal’ could be to encrypt its statement into a code which only the priest can decode back into human language. But Heraclitus says that the ‘lord’ does neither of these things, but rather produces a sign (whose meaning is of course indefinite). Any interpretation or translation of that sign into more precise language may clarify its pragmatic meaning, but loses the vagueness which makes the oracular language archetypal. Consequently a vast number of more or less valid statements can be generated by the interpretive process.

Heraclitus was famous for the seemingly cryptic quality of his own statements, an effect enhanced by the fragmentary nature of his works as we now have them. His intent in the fragment quoted above may have been ‘to justify his own oracular and obscure style’ (Kirk and Raven 1957, 212). But this style is common to many scriptural texts, such as the Tao Te Ching or the Gospel of Thomas; the seedlike quality that renders them inexhaustible is precisely their vagueness.

As for the process of way-making (dao),

It is ever so indefinite and vague.

Though vague and indefinite,

There are images within it.

Though indefinite and vague,

There are events within it.

Though nebulous and dark,

There are seminal concentrations of qi within it.— Dao De Jing 21, tr. Ames and Hall

Qi … cannot be resolved into any kind of spiritual-material dichotomy. Qi is both the animating energy and that which is animated. There are no “things” to be animated; there is only the vital energizing field and its focal manifestations. The energy of transformation resides within the world itself, and it is expressed in what Zhuangzi calls the perpetual “transforming of things and events (wuhua ).” It is this understanding of a focus-field process of cosmic change that is implicitly assumed in the Daodejing and other texts of this period as a kind of common sense.[next]— Ames and Hall 2002, 63

It was Rosen who wrote the book on ‘anticipatory systems,’ but it has been widely recognized that anticipation is the key to guidance. Michael Polanyi, for instance, remarked that our ‘whole set of faculties—our conceptions and skills, our perceptual framework and our drives—’ amount to ‘one comprehensive power of anticipation’ (Polanyi 1962, 103). Our meaning-cycle diagram is a way of picturing the form of that power, and the following passage from Polanyi could serve as a caption to it:

Why do we entrust the life and guidance of our thoughts to our conceptions? Because we believe that their manifest rationality is due to their being in contact with domains of reality, of which they have grasped one aspect. This is why the Pygmalion at work in us when we shape a conception is ever prepared to seek guidance from his own creation; and yet, in reliance on his contact with reality, is ready to re-shape his creation, even while he accepts its guidance. We grant authority over ourselves to the conceptions which we have accepted, because we acknowledge them as intimations— derived from the contact we make through them with reality— of an indefinite sequence of novel future occasions, which we may hope to master by developing these conceptions further, relying on our own judgment in its continued contact with reality. The paradox of self-set standards is re-cast here into that of our subjective self-confidence in claiming to recognize an objective reality.— Polanyi (1962, 104)

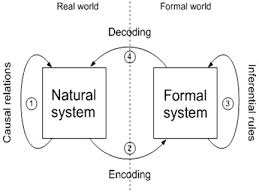

Here is one version of Rosen's original (1991) diagram (described in Chapter 9):

Howard Pattee – who was working with Rosen at the Center for Theoretical Biology at Buffalo in the early 1970s, when he was developing the ideas in Anticipatory Systems – told me in an email that Rosen first developed his diagram as a graphical representation of Heinrich Hertz’s description of the modeling process:

We form for ourselves images or symbols of external objects; and the form which we give them is such that the logically necessary (denknotwendigen) consequents of the images in thought are always the images of the necessary natural (naturnotwendigen) consequents of the thing pictured.This confirms Einstein's point that the ‘natural system’ we are modeling is unknowable in the sense that the real causes of systemic behavior are not directly observable but only (and fallibly) inferred. In the Rosen diagram above, the correspondence which defines the modeling relation as such is between the inferred ‘causal relations’ (arrow #1) and the ‘logically necessary consequents of the images in thought’ (arrow #3, ‘inferential rules’). Both the ‘relations’ and the ‘rules’ would count as legisigns in Peirce's 1903 terminology.For our purpose it is not necessary that they [images] should be in conformity with the things in any other respect whatever. As a matter of fact, we do not know, nor have we any means of knowing, whether our conception of things are in conformity with them in any other than this one fundamental respect.— Hertz, The Principles of Mechanics, 1-2 (New York: Dover, 1984; original German edition, Prinzipien Mechanik, 1894)

Both inference and causation are processes: in science, any relevant act of observation takes time. In fact, every “observation” or “measurement” in science must consist of (at least) two measurements: one of the initial conditions, and another (some time later) after the system has “behaved” in the situation we have chosen to focus on. What we call ‘the measurement’ is really the difference between these two measurements (even if it is zero because the system has not changed within the time frame). This is what Bateson calls ‘news of a difference’ and Rosen calls ‘encoding’ (arrow #2). A theoretical model “works” when that difference corresponds to some specific change between states of the theoretical image, some aspect of the model's dynamics.

Pattee adds that the diagram ‘also does not make clear that in a biological system the consequent of the model can be used to control its own state. The genetic description is a kind of model that exercises this kind of control of its own synthesis. This dependence of life on models or descriptions is what motivates the field of biosemiotics.’ A model that exercises this kind of control in “real time” is what i call a guidance system.

Diagrams equivalent to the gnoxic meaning-cycle diagram, or to Rosen's, abound in many of the sources drawn upon by Turning Signs. Evan Thompson's (2007, 47) is essentially an upside-down mirror image of the same diagram. Loewenstein's (1999, 287) diagram of the ‘cybernetic loop’ governing cell communication is equivalent if rotated 90° counterclockwise. A diagram by Floyd Merrell (2003, 172) is another mirror image of Rosen's. And so on.

[next]

[next]During perceptual experience, association areas in the brain capture bottom-up patterns of activation in sensory-motor areas. Later, in a top-down manner, association areas partially reactivate sensory-motor areas to implement perceptual symbols. The storage and reactivation of perceptual symbols operates at the level of perceptual components – not at the level of holistic perceptual experiences. Through the use of selective attention, schematic representations of perceptual components are extracted from experience and stored in memory (e.g., individual memories of green, purr, hot). As memories of the same component become organized around a common frame, they implement a simulator that produces limitless simulations of the component (e.g., simulations of purr). Not only do such simulators develop for aspects of sensory experience, they also develop for aspects of proprioception (e.g., lift, run) and for introspection (e.g., compare, memory, happy, hungry).The idea behind Barsalou’s ‘simulators’ and ‘simulations’ here is that the brain, having learned from perceptual and/or proprioceptive experiences, is able to recreate or rehearse versions of those experiences in the absence of the original perceptual or proprioceptive stimulus. In emphasizing the perceptual basis of conceptual systems, Barsalou does not dissolve the distinction between perception and cognition. Perceptual symbols are the permanent cognitive traces (in the form of activation potentials) of fleeting perceptual experiences. Barsalou emphasizes the continuity between non-human and human conceptual representational systems, implicitly granting (and I agree) that non-human animals have conceptual systems. It is known that many animals have attention and both working and long-term memory, and it seems likely that they can apply these to the formation of Barsalovian perceptual symbols to ‘produce useful inferences about what is likely to occur at a given place and time, and about what actions will be effective’ (Barsalou 1999, pp. 606–607).(Barsalou 1999, p. 577)— James R. Hurford (2007, 55-6)

Because information has to be carried by structures, it is lost when the carriers disperse (second energy law). Therefore, emergy is required to maintain information.… So in the long run, maintaining information requires a population operating an information copy and selection circle …. The information copies must be tested for their utility. Variation occurs in application and use because of local differences and errors. Then the alternatives that perform best are selected, and the information of the selected systems is extracted again. Many copies are made so that the information is broadly shared and used again, completing the loop. In the process, errors are eliminated, and improvements may be added in response to the adaptation to local variations.The information process, which is the ‘application and use’ of “stored” or potential information to actually inform the guidance system, is the crucial part of this copy and selection circle; ‘the ability to retrieve and use information is rapidly diluted as the number of stored information items increases. To accumulate information without selection is to lose its use’ (Odum 2007, 241). [next]— H.T. Odum (2007, 88)

It seems certainly the truest statement for most languages to say that a symbol is a conventional sign which being attached to an object signifies that that object has certain characters. But a symbol, in itself, is a mere dream; it does not show what it is talking about. It needs to be connected with its object. For that purpose, an index is indispensable. No other kind of sign will answer the purpose. That a word cannot in strictness of speech be an index is evident from this, that a word is general – it occurs often, and every time it occurs, it is the same word, and if it has any meaning as a word, it has the same meaning every time it occurs; while an index is essentially an affair of here and now, its office being to bring the thought to a particular experience, or series of experiences connected by dynamical relations. A meaning is the associations of a word with images, its dream exciting power. An index has nothing to do with meanings; it has to bring the hearer to share the experience of the speaker by showing what he is talking about. The words this and that are indicative words. They apply to different things every time they occur. It is the connection of an indicative word to a symbolic word which makes an assertion.In any given context, the set of “things” we can make assertions about is called the universe of discourse. Peirce explained this in his BD definition of ‘Universe (in logic)’:— Peirce, CP 4.56 (1893)

Universe of discourse, of a proposition, &c.: In every proposition the circumstances of its enunciation show that it refers to some collection of individuals or of possibilities, which cannot be adequately described, but can only be indicated as something familiar to both speaker and auditor. At one time it may be the physical universe … at another it may be the imaginary ‘world’ of some play or novel, at another a range of possibilities.… It does not seem to be absolutely necessary in all cases that there should be an index proper outside the symbolic terms of the proposition to show what it is that is referred to; but in general there is such an index in the environment common to speaker and auditor.

‘A common noun [such] as “man,” standing alone, is certainly an index, but not of the object it denotes. It is an index of the mental object which it calls up. It is the index of an icon; for it denotes whatever there may be which is like that image’ (Peirce, EP2:17-18). The noun points to an iconic feature of the Model (as explained in Chapter 9), not directly to something existing in the World external to the Model. The genuine Index represents a real duality or Secondness. ‘Genuine secondness is dynamical connection; degenerate secondness is a relation of reason, as a mere resemblance’ (EP1:280, W6:211).

It is desirable that you should understand the difference between the Genuine and the Degenerate Index. The Genuine Index represents the duality between the representamen and its object. As a whole it stands for the object; but a part or element of it represents [it] as being the Representamen, by being an Icon or analogue of the object in some way; and by virtue of that duality, it conveys information about the object. The simplest example of a genuine index would be, say, a telescopic image of a double star. This is not an icon simply, because an icon is a representamen which represents its object by virtue of its similarity to it, as a drawing of a triangle represents a mathematical triangle. But the mere appearance of the telescopic image of a double star does not proclaim itself to be similar to the star itself. It is because we have set the circles of the equatorial so that the field must by physical compulsion contain the image of that star that it represents that star, and by that means we know that the image must be an icon of the star, and information is conveyed. Such is the genuine or informational index.Thus a proper name is a degenerate index because knowing a person's name does not by itself provide you with any information about that person. A noun standing alone, whether common or proper, does not provide any information. A noun can function as a genuine index only when circumstances enable its interpreter to make a double connection, a factual or ‘real’ connection and a mental connection, with what it denotes.A Degenerate Index is a representamen which represents a single object because it is factually connected with it, but which conveys no information whatever. Such, for example, are the letters attached to a geometrical or other diagram. A proper name is substantially the same thing; for although in this case the connection of the sign with its object happens to be a purely mental association, yet that circumstance is of no importance in the functioning of the representamen.— Peirce, EP2:171-2

Of course ‘genuine, degenerate’ and ‘informational’ are relative terms; all signs function triadically in some sense or they couldn't be signs at all, yet in actual semiosis or communication, all signs are degenerate (or ‘incomplete’) to some degree. In systemic terms, we could say than an index is genuine to the extent that it Informs the system about the world external to it. Whatever is genuinely Second to a system is external to it; ‘degenerate seconds may be conveniently termed Internal, in contrast to External seconds, which are constituted by external fact, and are true actions of one thing upon another’ (EP1:254). External seconds enter into ‘real relations’ as opposed to what the medieval logicians called ‘relations of reason’ (EP1:253).

Logical necessity is the necessity that a sign should be true to a real object; and therefore there is logical reaction in every real dyadic relation.… There are, however, degenerate dyadic relations,— degenerate in the sense in which two coplanar lines form a degenerate conic,— where this is not true. Namely, they are individual relations of identity, such as the relation of A to A. All mere resemblances and relations of reason are of this sort.The Dynamical Object of a genuine sign, being ‘an object of actual Experience’ (SS 197), is always outside of the interpreting system in the sense of being beyond its control – and therefore able to make a real difference to its self-control, its habit-system, its ‘inner law.’ [next]— Peirce, EP2:306

A clear-cut example is seen in the genetic code. The code is made up of triplets of nucleotide bases, of which there are four kinds: G, C, A, and T. Each triplet, or codon, specifies one of the twenty different amino acids that make up a protein. Since there are sixty-four different possible codons – actually sixty-one, if we leave out three stop codons – which makes a total of more than one per amino acid, the code words are degenerate. For example, the third position of many triplet codons can contain any one of the four letters or bases without changing their coding specificity. If it takes a sequence of three hundred codons to specify a sequence of one hundred amino acids in a protein, then a large number of different base sequences in messages (approximately 3100) can specify the same amino-acid sequence. Despite their different structures at the level of nucleotides, these degenerate messages yield the same protein.This biological usage of the term degenerate is quite different from the mathematical sense used by Peirce (polyversity strikes again!); here degeneracy refers to the ability of different structures to serve the same systemic function. As Ernst Mayr (1988, 141) points out, this complicates evolutionary theory because it means that mutations consisting of base-pair substitutions can be ‘neutral’ with respect to selection. But this inconvenience is not one we could dispense with, as Edelman goes on to explain:— Edelman (2004, 43-4)

Degeneracy is a ubiquitous biological property. It requires a certain degree of complexity, not only at the genetic level as I have illustrated above, but also at cellular, organismal, and population levels. Indeed, degeneracy is necessary for natural selection to operate and it is a central feature of immune responses. Even identical twins who have similar immune responses to a foreign agent, for example, do not generally use identical combinations of antibodies to react to that agent. This is because there are many structurally different antibodies with similar specificities that can be selected in the immune response to a given foreign molecule.What Edelman calls degeneracy is called ‘multiple realizability’ by Deacon (2011, 29), who gives the example of oxygen transport in circulatory systems. This is realized by hemoglobin in humans and other mammals, but by other molecules in (for instance) clams and insects.

For us humans, degeneracy is perhaps most interesting for its role in generating conscious experience. Neural processes related to the experience of having a world can be analyzed in terms of “maps,” and the relations among these maps turn out to be degenerate. Visual experience alone may involve dozens of them, cooperating (in Edelman's theory) by means of

mutual reentrant interactions that, for a time, link various neuronal groups in each map to those of others to form a functioning circuit.… But in the next time period, different neurons and neuronal groups may form a structurally different circuit, which nevertheless has the same output. And again, in the succeeding time period, a new circuit is formed using some of the same neurons, as well as completely new ones in different groups. These different circuits are degenerate – they are different in structure but they yield similar outputs …— Edelman (2004, 44-5)

By its very nature, the conscious process embeds representation in a degenerate, context-dependent web: there are many ways in which individual neural circuits, synaptic populations, varying environmental signals, and previous history can lead to the same meaning.— Edelman (2004, 105)

Even within a given context, there are many ways for implications or intimations to become explicit. So naturally different texts can yield the same meaning, and different verbal expressions of belief can yield the same practice.

Another aspect of this degeneracy is that different theories may articulate the same implicit models: for example, Edelman's ‘theory of neuronal group selection’ appears to have the same significance as Bateson's theory of ‘the great stochastic processes’: in each case evolution and learning are processes which differ only in time scale. ‘In this theory,’ says Edelman,

the variance and individuality of brains are not noise. Instead, they are necessary contributors to neuronal repertoires made up of variant neuronal groups. Spatiotemporal coordination and synchrony are provided by reentrant interactions among these repertoires, the composition of which is determined by developmental and experiential selection.The necessity of ‘variance and individuality’ is not confined to brains. ‘The biologist is constantly confronted with a multiplicity of detailed mechanisms for particular functions, some of which are unbelievably simple, but others of which resemble the baroque creations of Rube Goldberg’ (Lewontin 2001, 100). Degeneracy rules – and not only in a figurative sense, for it plays a crucial role in ‘the control hierarchy which is the distinguishing characteristic of life’ (Pattee 1973, 75). This differs from the hierarchy of scale in that it ‘implies an active authority relation of the upper level over the elements of the lower levels’ (75-6). This relation is also known as ‘supervenience’ or ‘downward causality’ (Pattee 1995), which is part of Freeman's ‘circular causality’, as it ‘amounts to a feedback path between levels’ (Pattee 1973, 77).— Edelman (2004, 114)

The development process in a multicellular organism offers an example. Each cell carries a copy of the entire genome in its nucleus; how does it manage to differentiate into a liver cell, or a blood cell, or a specific type of neuron? It receives ‘chemical messages from the collections of cells that constrain the detailed genetic expression of individual cells that make up the collection.’ Like all messages, these are coded, but the coding/decoding function is not to be found in the structure of the molecules carrying the message, whether they be enzymes, hormones or DNA. Likewise the control function is not found in any special qualities of those elements of the system which appear to be in ‘control’: rather it is found at ‘the hierarchical interface between levels’ (Pattee 1973, 79). The control function is degenerate in that the choice of particular elements to exercise control is to some degree arbitrary, and a different choice does not make a significant difference in the control itself.

Of course, this is also the general nature of social control hierarchies. As isolated individuals we behave in certain patterns, but when we live in a group we find that additional constraints are imposed on us as individuals by some ‘authority.’ It may appear that this constraining authority is just one ordinary individual of the group to whom we give a title, such as admiral, president, or policeman, but tracing the origin of this authority reveals that these are more accurately said to be group constraints that are executed by an individual holding an ‘office’ established by a collective hierarchical organization.— Pattee 1973, 79

The control function is not a property of, and does not belong to, the individual who executes it. When someone tries to appropriate that function for himself, we call him a tyrant – a person who tries to control others for his own sake instead of serving the higher level of organization.

The polysemy of the term hierarchy is rooted in that of the Greek ἀρχη, which can mean either ‘a beginning, origin’ or ‘power, dominion, command’ (LSG). In English, first has a similar ambiguity: it can denote either one end of a time-ordered series or the “top” spot in a ranking order.

In speaking of ‘control functions,’ we often need to distinguish between two kinds of ‘law’ or ‘rule,’ which we may call logos and nomos. The logos (or ‘logic’) of a system is its self-organizing function, while nomos is ‘assigned’ (LSG) artificially rather than arising naturally. Nomos is the kind of law which is formulated and “ordered” to be obeyed or “observed,” while the “laws of nature” are formulated (by science) in order to explain why nature does what it is observed to be doing already. The distinction is denied by creationists, for whom nature itself is artificial (having been intentionally designed and implemented by a God existing prior to it), and perhaps by some who consider every formulation of science to be a disguised assertion of power. And the distinction is indeed problematic, because nomos in Greek can mean ‘usage’ or ‘custom’ as well as ‘law’ and ‘ordinance’ (LSG again). Are the “rules” of a “natural” language nomoi or logoi? I would say that the deepest grammatical rules are examples of logos, while the more ephemeral standards of usage are much more arbitrary, and therefore examples of nomos, even before they are formalized. But the boundary between them is fuzzy. You could put the question this way: How natural is human nature?

[next]

One consequence of polyversity is that, as the ancient sage put it, ‘the name that can be named is not the eternal name’ (Tao Te Ching 1). Differences arise between presence and representation. This becomes clear when we focus on representation by making words the objects of our attention and recognize them as signs.

The pit of a peach or cherry has nothing to do with the kind of pit you can dig with a shovel. We can say then that these are two different words with respect to denotation, although they are the same with respect to both spoken and written form. Thus we can pit one kind of difference against another. Likewise, something moving fast is in rapid motion, but something stuck fast is not moving at all. To quicken something is to bring it to life, and thus make it “quicker,” but to fasten something is to immobilize it, not to make it “faster.” And then there's the verb fast, which has yet another meaning, involving neither movement nor the lack of it.

Since the number of one-syllable phonemes distinguishable in English (or any language) is finite, it is predictable that as the language develops, one sound will accidentally get attached to two or more different concepts. Then we have two words that happen to sound exactly the same: homonyms, as they are called in linguistics. Homonymy is different from polysemy, in which one word can have many “senses” or “meanings”; yet ‘there is an extensive grey area between the concepts’ (McArthur 1992, 795).

[next]

We can begin with the recognition that both consciousness and semiosis are continuous processes. This led Peirce in 1873 (W3:72-5, CP 7.351-3) to a holistic explanation of determination:

It will easily be seen that when this conception is once grasped the process of the determination of one idea by another becomes explicable. What is present to the mind during the whole of an interval of time is something generally consisting of what there was in common in what was present to the mind during the parts of that interval.… There is besides this a causation running through our consciousness by which the thought of any one moment determines the thought of the next moment no matter how minute these moments may be. And this causation is necessarily of the nature of a reproduction; because if a thought of a certain kind continues for a certain length of time as it must do to come into consciousness the immediate effect produced by this causality must also be present during the whole time, so that it is a part of that thought. Therefore when this thought ceases, that which continues after it by virtue of this action is a part of the thought itself. In addition to this there must be an effect produced by the following of one idea after a different idea; otherwise there would be no process of inference except that of the reproduction of the premises.This anticipates Peirce's later statements to the effect that the antecedent-consequent relation is the essential concept for explaining the process of determination. But does this concept at the heart of inference also explain causality in the physical realm? Peirce addressed this question under the rubric of ‘the logic of events’ in his Cambridge Conferences lecture series of 1898. In the sixth lecture, on ‘Causation and Force,’ he argued that causation must be regarded as a relation between facts, not between events (RLT 198). As he put it later,

That which is caused, the causatum, is, not the entire event, but such abstracted element of an event as is expressible in a proposition, or what we call a “fact.” The cause is another “fact.”He followed this up in 1906:

A state of things is an abstract constituent part of reality, of such a nature that a proposition is needed to represent it. There is but one individual, or completely determinate, state of things, namely, the all of reality. A fact is so highly a prescissively abstract state of things, that it can be wholly represented in a simple proposition, and the term “simple,” here, has no absolute meaning, but is merely a comparative expression.EP2:378

All our knowledge, all our thought, is in signs – including our knowledge of what happens ‘whenever one thing acts upon another.’ That action may be essentially dyadic, but our cognition of it must be the triadic action of semiosis; only semiotic determination can render physical causation intelligible.

Peirce argued (EP2:392) that the best way of ‘determining the precise sense which we are to attach to the term determination’ is to realize that a sign whose meaning was completely determinate would leave ‘no latitude of interpretation’ at all, ‘either for the interpreter or for the utterer.’ This makes the definition of determination ‘turn upon the interpretation’ (EP2:393). This way of defining determination applies to ‘anything capable of indeterminacy’ (EP2:392) – but if ‘everything indeterminate is of the nature of a sign’ (EP2:392 fn), then the process of cognitive determination (or learning) is just a special case of semiosis.

Peirce went on to argue – based on the analysis represented by his Existential Graphs – that semiosis at any level of complexity amounts to a mutual determination of signs, paradigmatically of Antecedent and Consequent.

[next]

The consequence is that Mill is obliged to define the cause as the totality of all the circumstances attending the event. This is, strictly speaking, the Universe of being in its totality. But any event, just as it exists, in its entirety, is nothing else but the same Universe of being in its totality.Peirce mentions this merely to explain why Mill's usage of the word ‘cause’ renders it a useless concept with no pragmatic value. Yet the same idea (at least, we may use this language) was developed and explained at great length in several classic texts of the Hua-Yen school of Buddhist philosophy.— Peirce, EP2:315

The Hua-Yen doctrine shows the entire cosmos as one single nexus of conditions in which everything simultaneously depends on, and is depended on by, everything else. Seen in this light, then, everything affects and is affected by, more or less immediately or remotely, everything else; just as this is true of every system of relationships, so is it true of the totality of existence. In seeking to understand individuals and groups, therefore, Hua-yen thought considers the manifold as an integral part of the unit and the unit as an integral part of the manifold; one individual is considered in terms of relationships to other individuals as well as to the whole nexus, while the whole nexus is considered in terms of its relation to each individual as well as to all individuals. The accord of this view with the experience of modern science is obvious, and it seems to be an appropriate basis upon which the question of the relation of science and bioethics—an issue of contemporary concern—may be resolved.Cleary's reference to ‘the experience of modern science’ is vague, but no doubt represents statements such as this one: ‘All evolution is coevolution, since the species of an ecosystem are all interdependent’ (Morowitz 2002, 93). But the more specific an inquiry into causation, the more sharply it focuses on facts abstracted from events rather than ‘the whole nexus.’ [next]— Cleary (1983, 532)

Meaning is formed in the interaction between felt experiencing and something that functions symbolically. Feeling without symbolization is blind; symbolization without feeling is empty.Gendlin's second sentence closely resembles a famous Kantian statement, quoted as follows by Cassirer (1944, 56): ‘Concepts without intuitions are empty; intuitions without concepts are blind.’ Is Gendlin then repeating something already said by Kant? That depends on whether ‘intuitions’ are equivalent to ‘feeling’ and ‘concepts’ to ‘symbolization.’ [next]

While a sign is functioning symbolically within your act of meaning – i.e. while it is in actual use – you can't pay attention to, or even mention, its function.

You can't have your use and mention it too.— Hofstadter (1985, 9)

We cannot look at our standards in the process of using them, for we cannot attend focally to elements that are used subsidiarily for the purpose of shaping the present focus of attention.In scientific practice, you can't make your measurement (observation) and describe your measuring device at the same time:— Michael Polanyi (1962, 183)

even though any constraint like a measuring device, M, can in principle be described by more detailed universal laws, the fact is that if you choose to do so you will lose the function of M as a measuring device. This demonstrates that laws cannot describe the pragmatic function of measurement even if they can correctly and completely describe the detailed dynamics of the measuring constraints.Likewise in the realm of cognition or experiencing, attention to what you know precludes attention to the process currently generating that knowledge; the form or image which actually occupies your attention blinds you to the ungraspable process of experiencing, and (temporarily) to other forms or images it could possibly be generating at the moment. Thomas 83 gives mystical expression to this idea: ‘The light of the Father will reveal itself, but his image is hidden by his light.’ Or as Moses Cordovero put it, ‘revealing is the cause of concealment and concealment is the cause of revealing’ (Scholem 1974, 402). [next]— Howard Pattee (2001)

Sincerity is incommunicable because it becomes insincere by being communicated. Communication presupposes the difference between information and utterance and the contingency of both.[next]— Niklas Luhmann (1995, 150)

refers to each individual of a class separately, and not to these individuals as making up the whole class. The distributive acceptation of such an adjective as all is that in which whatever is said of all is said of each: opposed to collective acceptation, in which something is said of the whole which is not true of the parts.— CD ‘Distributive’

Now it is precisely the pragmatist's contention that symbols, owing their origin (on one side) to human conventions, cannot transcend conceivable human occasions. At any rate, it is plain that no possible collection of single occasions of conduct can be, or adequately represent all conceivable occasions. For there is no collection of individuals of any general description which we could not conceive to receive the addition of other individuals of the same description aggregated to it. The generality of the possible, the only true generality, is distributive, not collective.— from a dialogue by Peirce, CP 5.532 (c. 1905)

A human individual is both a member or part of Humanity and a whole embodiment or instance of Humanity. In logical terms, these are the collective and distributive senses of “human,” respectively. A typical community is a larger part of Humanity in the collective sense, but only indirectly related to actual human feeling and experience.

A corporation is still less human, though it may be deemed a “person” for legal purposes. Modern corporations are degenerate persons, legal fictions created for a specific and very limited purpose, namely to maximize financial profits while minimizing risk for the shareholders. In order to develop real personalities they would have to learn from their interactions with others, as genuine persons do – interactions based on empathy. But the growth and development of empathy is entirely different from what economists call “growth.”

Many myths, legends and comprehensive works of fiction, such as Blake's prophetic books and Finnegans Wake, portray the cosmos as a reflection or expression of the human bodymind, and the history of humanity as the biography (or the dream) of a universal Human Being. This mythical being is singular, one of a kind, like ‘the all of reality’: universal, but not general in either the collective or the distributive mode.

In the mythic dimension of science, the ultimate community of inquiry is more than just humanity: it is the whole system of all experiencing subjects, the cast of characters of God's play or Gaia's dream, or .....

[next]

Looking at language itself is like looking at a mirror rather than at the reflection in a mirror, or looking at a window rather than through it: the linguistic phenomenon ceases to be transparent and we focus on its dynamics rather than those of “the world.” This can raise its automatic functions into consciousness and restore awareness of the habits we have taken for granted.

For instance, we can look at familiar idioms which we normally use automatically, and try to trace their peculiarities back to the root. Consider the English expression “back and forth”: why is it not “forth and back”? Do we normally imagine that kind of motion as beginning with the return? Maybe we do: perhaps an irreversible “going forth” is the default kind of motion, as it were, and only when this is interrupted by a “coming back” do we notice a distinctive pattern – which we then call “back-and-forth.” This would explain why the practice of “mindfulness” can be defined as “coming back to the present.”

But then why do we say that someone tumbles “head over heels”? Taken “literally,” this expression would be equivalent to “upside up”; “upside down” (or “downside up”) would be better expressed as “heels over head.” Well, maybe the idiom is dominated by the dynamic (rather than the static positional) sense of over – as in “fall over,” “turn over” etc. – and we simply ignore the order of the nouns. Or we habitually put “head” at the head of an expression, as in “headlong,” “head start” and so on. The reference to the head as a body part is far in the background in most of these expressions.

There's an element of chance in any evolutionary process, including historical changes of word meaning. Idiomatic and conventional expressions are full of “frozen accidents.” Some accidents are more likely, more ‘motivated,’ than others (Lakoff 1987, Sweetser 1990), but all are unruly to some degree, as is life itself.

[next]

Consider for instance Ray Jackendoff's (1992) essay on ‘The Problem of Reality,’ which explains why ‘constructivist’ psychology is a more viable model of our relationship to external reality than analytical philosophy which tries to base meaning on ‘truth-conditions.’ (He does not consider the Peircean alternative that the sense of reality is grounded in a ‘dyadic consciousness.’) Toward the end of the essay he takes up an objection to the constructivist view, stated as a more or less rhetorical question:

If reality is observer-relative, how is it that we manage to understand one another? (This objection is essentially Quine's (1960) ‘indeterminacy of radical translation,’ now applied at the level of the single individual.)Jackendoff gives two answers to this. Translating the first into my own terms: assuming that ‘we’ are both human, our common biological nature makes it a good bet that our meaning spaces are similar. (Jackendoff uses ‘combinatorial space’ where i use ‘meaning space.’)— Jackendoff (1992, 173)

The second answer to this objection is that we don't always understand each other, even when we think we do. This is particularly evident in the case of abstract concepts. Quine's indeterminacy of radical translation in a sense does apply when we are dealing with world views in areas like politics, religion, aesthetics, science, and, I guess, semantics. These are domains of discourse in which the construction of a combinatorial space of concepts is underdetermined by linguistic and sensory evidence, and innateness does not rush in to the rescue.Since we are now at work in one of those domains of discourse, it is possible that Jackendoff's ‘combinatorial space’ is more different from my ‘meaning space’ than i think it is. Investigating that possibility would involve exploring the context of each usage more fully, always guided by Peirce's ‘maxim of pragmatism.’ Would that investigation be worthwhile? Who knows? [next]

For example, take Chapter 62 of the Tao Te Ching. Waley gives us ‘Tao in the universe is like the south-west corner in the house,’ which he informs us in a footnote is ‘Where family worship was carried on; the pivotal point round which the household centred.’ Chan, on the other hand, renders the verse ‘Tao is the storehouse of all things,’ noting that the southwest corner of the house is ‘where treasures were stored.’ These two different understandings of ‘the southwest corner’ are perhaps reconciled in the English/Feng translation: ‘Tao is the source of the ten thousand things.’ But this translation loses the specificity of ‘the south-west corner.’

Even if we believe that there is such a thing as a “correct” translation of a verse, we have no way of identifying it in any specific case. To do that would require a “God's-eye view” that could take in not only both languages in the relevant historical context, but also the intent of both author and reader, as shaped by their respective cultures and experiences. Thus the notion of a “correct translation” is of little pragmatic use.

[next]

Typical usage of “progress” (as a noun or verb) puts a positive spin on the idea of a progression, i.e. a forward motion: we generally use it in reference to a process or sequence in which later points (or states) are improvements over earlier points in the sequence. The same happens with “success”: it generally refers to a positive outcome of a succession of acts.

But as Robert Theobald (1997) and many others have pointed out, our “success” in exploiting resources for our own purposes is now the greatest obstacle to our well-being. Long before that (1940), Walter Benjamin effectively reversed the spin on “progress” in his Angelus Novus, which was recomposed by Laurie Anderson in ‘The Dream Before’ on her 1989 album Strange Angels, and recycled by Adrian Ivakhiv in Shadowing the Anthropocene (2018, 67). Artists and philosophers like to work against the ordinary spin on words and images.

We see the positivizing trend in the evolution of spin on “happy” in English. Things happen, but it's only if the outcome is positive for us, if our luck is good, that we call the events (or ouselves) “happy” or “lucky.” We don't call ourselves “happy” when (as we say) “shit happens.” (In English, the old usage of “happy” as referring to events rather than emotional states has almost disappeared, but we still use “lucky” both ways.) Similarly “fortune” can be kind or unkind, and someone who “tells your fortune” may bring good news or bad news, but if you are “fortunate,” that means the news is good.

Other words have spun in the opposite direction. “Destiny” and “fate” are equally beyond our control, but the latter word has ominous overtones, and a “fatal” event is about as negative as anything can be for mortals.

A successful translation from one language into another would translate the spin of each phrase as well as its more “objective” reference – but the shifting relationships between sense and spin are rarely parallel across languages, and even differ between one person and another. This is yet another reason why a perfectly “successful” translation is an ideal that can hardly ever be realized.

[next]

The lexicon of the new language would reflect the composition of reality and in it every word should have a definite and univocal meaning, every content should be represented by one and only one expression, and the contents were not supposed to be the products of fancy, but should represent only every really existing thing, no more and no less.— Eco (1995, 216)

Peirce made a much more pragmatically realistic proposal in his ‘ethics of terminology’: in the vocabulary of any branch of science, ‘each word should have a single exact meaning’ (EP2:264) – but this requirement should not be applied too rigidly, even within the sciences, because words are symbols, and symbols grow.

As to the ideal to be aimed at, it is, in the first place, desirable for any branch of science that it should have a vocabulary furnishing a family of cognate words for each scientific conception, and that each word should have a single exact meaning, unless its different meanings apply to objects of different categories that can never be mistaken for one another. To be sure, this requisite might be understood in a sense which would make it utterly impossible. For every symbol is a living thing, in a very strict sense that is no mere figure of speech. The body of the symbol changes slowly, but its meaning inevitably grows, incorporates new elements and throws off old ones. But the effort of all should be to keep the essence of every scientific term unchanged and exact; although absolute exactitude is not so much as conceivable. Every symbol is, in its origin, either an image of the idea signified, or a reminiscence of some individual occurrence, person or thing, connected with its meaning, or is a metaphor. Terms of the first and third origins will inevitably be applied to different conceptions; but if the conceptions are strictly analogous in their principal suggestions, this is rather helpful than otherwise, provided always that the different meanings are remote from one another, both in themselves and in the occasions of their occurrence. Science is continually gaining new conceptions; and every new scientific conception should receive a new word, or better, a new family of cognate words. The duty of supplying this word naturally falls upon the person who introduces the new conception; but it is a duty not to be undertaken without a thorough knowledge of the principles and a large acquaintance with the details and history of the special terminology in which it is to take a place, nor without a sufficient comprehension of the principles of word-formation of the national language, nor without a proper study of the laws of symbols in general. That there should be two different terms of identical scientific value may or may not be an inconvenience, according to circumstances. Different systems of expression are often of the greatest advantage.We might say that ‘growth’ of meaning in a symbol system, like development of the brain, is a matter of progress toward optimal (not maximal!) connectivity. Throwing off old elements is part of the growth of meaning, just as it is essential to ‘the plasticity of the child's mental habits’ (recalling Chapter 1). For a symbol, as for a population of neurons, too many connections would be counterproductive.EP2:264-5, CP 2.222

In logical terms, a word or other symbol ‘grows’ when either its breadth increases (thus revealing previously unknown relations among different subjects) or its logical depth increases (so that the symbol is more intimately connected with the rest of the guidance system). Iconic and indexical signs, as opposed to symbols, may not be alive in themselves, but they provide the freedom and the forcefulness (respectively) necessary for the life of symbols in which they are involved.

Peirce's concept of the ‘perfect sign’ reflects the ‘living’ quality of symbols rather than the rigidity of a ‘perfect language’ as conceived by Comenius. ‘Such perfect sign is a quasi-mind. It is the sheet of assertion of Existential Graphs’ (EP2:545). A graph scribed on the sheet of assertion is a ‘Pheme,’ i.e. a proposition or Dicisign (CP 4.538). Stjernfelt (2014, 85) points out as a ‘central issue in Peircean logic that the reference of a Dicisign is taken to be relative to a selected universe of discourse—a model—consisting of a delimited set of objects and a delimited set of predicates, agreed upon by the reasoners or communicating parties, often only implicitly so.’ The plurality of universes is an aspect of polyversity.

In Peirce's doctrine of Dicisigns, the plurality of representations is evident in the fact that the same objects may be addressed using different semiotic tools, highlighting different aspects of them. … If you accept only one language, the question of the relation of this language to its object cannot be posed outside of this language—and truth becomes ineffable. If several different, parallel approaches to the same object are possible, you can discuss the properties of one language in another, and you may use the results of one semiotic tool to criticize or complement those of another. Even taking logic itself as the object, Peirce famously did this, developing several different logic formalisms (most notably the Algebra of Logic and the Existential Graphs), unproblematically discussing the pros and cons of these different representation systems.—Stjernfelt 2014, 85(fn)