I never understand anything until I have written about it.

— Horace Walpole

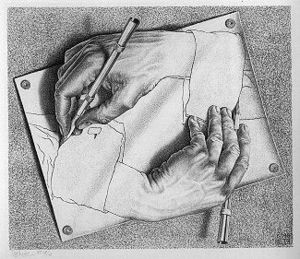

For writers, Annie Dillard offers a more detailed view of the process in The Writing Life (1989). Eugene Gendlin’s focusing is a technique for dipping into the ‘implicit intricacy’ which is the creative source of understanding, as illustrated in Chapter 4 by the experience of writing a poem. From this point of view, Walpole’s observation is that writing is a way of exploring the implicit intricacy by trying to make it explicit – even though simplexity (Chapter 11) guarantees that consciousness can never match the intricacy of the unconscious processes which it aims to explicate. The drawing is always simpler than its subject. Ray Jackendoff puts the point in linguistic terms:

Language use continually involves unconscious processes, both prior to and during conscious phases. So, although some unconscious processes (such as sensory processing) must precede awareness, not all do. In addition, unconscious representations if anything must be more highly articulated than those that appear in consciousness, not more ‘primitive’: compare the elaboration of unconscious linguistic structure with the degree of awareness one has of this structure.

— Jackendoff (1994, 90)

We use our knowledge of the language – or any semiotic system – without being conscious of that knowledge; and by using it, we become better acquainted with the intricacy of the objects of our signs, we understand them better, even though the symbols we generate do not contain that acquaintance. At best they can give us hints for consciously directing our attention.