… and animals, both wild and tame, feeding in the air or on the earth or in the water, all are born and come to their prime and decay in obedience to the ordinances of God; for, in the words of Heraclitus, ‘every creeping thing grazes at the blow of God’s goad’.

— Pseudo-Aristotle, De Mundo (Περὶ Κόσμου), tr. E.S. Forster (Oxford, 1914)

In the original Greek of Heraclitus, as quoted here by the author of On the Cosmos, there is no “God” and no “goad”. A more literal translation of πᾶν ἑρπετὸν πληγῇ νέμεται would be “All beasts [πᾶν ἑρπετὸν] are driven [νέμεται] by blows [πληγῇ].” But the verb νέμεται was ordinarily used with reference to herdsmen “tending”  their flocks or herds; driving the beasts to a pasture where they could ‘graze’ was a regular part of this “tending,” and this was often done with a stick like the one in the picture.

their flocks or herds; driving the beasts to a pasture where they could ‘graze’ was a regular part of this “tending,” and this was often done with a stick like the one in the picture.

This explains the grazing and the ‘goad’ in Forster’s translation. But the Greek does not specify who is delivering these benevolent ‘blows’ to the beasts. The context indicates that the class of “creeping things” includes not only domestic cattle but all animals throughout their life cycles, including wild and human animals as well (Kahn 1979, 194). Who or what drives the deer to their pasture? What kind of “blows” compel us to carry our own lives forward?

“Pseudo-Aristotle” tells us that all life cycles proceed according to ‘the ordinances of God,’ who is metaphorically the “pastor” driving us all to “pasture.” Others might substitute for those ordinances the laws of nature, governing everything impersonally. But if all animals are guided from within and powered by their own metabolism, it would seem that we are driven by internal “blows” or “motivations” rather than external forces, whether divine or natural. We are “driven” to dinner by the same “force” that drives the deer to their pasture, namely hunger.

But this is not the whole story either. We are all shaped, physically and mentally, by the same sacred laws of nature that formed the worlds we inhabit and the habits that inform our relations with the world and one another. These Laws have made us all anticipatory systems, and the “blows” driving us are the blows of experience, which happens to us as some kind of collision between our guidance systems and our circumstances. An experience feels real here and now because of the difference, the Secondness, between our own needs and the necessities of external world. But what really determines the kind of experience that strikes us at the moment is the Laws in their Thirdness.

For reality is compulsive. But the compulsiveness is absolutely hic et nunc. It is for an instant and it is gone. Let it be no more and it is absolutely nothing. The reality only exists as an element of the regularity. And the regularity is the symbol. Reality, therefore, can only be regarded as the limit of the endless series of symbols.

— Peirce, EP2:323

Our lack of control over existing things and actual events, their way of forcing themselves on our attention, is what makes them real to us at the moment. But the laws governing these things are equally real – or more real, considering that they will continue to determine what form the future will take long after the immediate past and present are gone. To the extent that we have self-control – that is, control over the form and the enforcement of our inner “laws” or habits – we can participate in this determination of the future. We never break the laws of nature, but we have ways of co-operating with it to realize imagined possibilities; and these may include our ways of responding to the “blows” of experience.

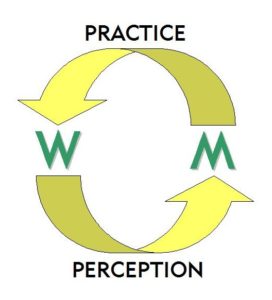

Life cycles, like meaning cycles, are governed by the reciprocity of practice and perception. They are driven by the “blows” of experience just as inquiries are set in motion by surprises. This is a law of nature which we can only symbolize in some kind of diagram. We can’t make a photograph of it as we can an existing ‘goad’ or an actual ‘blow.’ The image of ‘God’s goad’ confuses the regularity of law with the the force of law. A law (natural, human or divine) has a general form but can’t be adequately represented by any specific image – unless that image is read as a metaphor. Metaphors, in their aspiration to the generality of symbols, reveal those realities which images conceal by their very presence to our sense perception. Only symbols can express the Law turning the wheel of life.

Life cycles, like meaning cycles, are governed by the reciprocity of practice and perception. They are driven by the “blows” of experience just as inquiries are set in motion by surprises. This is a law of nature which we can only symbolize in some kind of diagram. We can’t make a photograph of it as we can an existing ‘goad’ or an actual ‘blow.’ The image of ‘God’s goad’ confuses the regularity of law with the the force of law. A law (natural, human or divine) has a general form but can’t be adequately represented by any specific image – unless that image is read as a metaphor. Metaphors, in their aspiration to the generality of symbols, reveal those realities which images conceal by their very presence to our sense perception. Only symbols can express the Law turning the wheel of life.

to be continued