What we call ‘knowledge’ is just that property of Rosen’s ‘anticipatory systems’ which enables them to anticipate successfully (to some degree). Karl Popper points in this direction when he says that ‘knowledge has often the character of expectations’ and that ‘most kinds of knowledge, whether of men or animals, are hypothetical or conjectural’ (Popper 1990, 32).

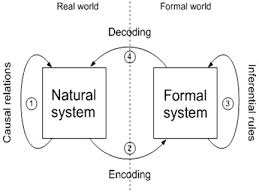

One rendering of Rosen’s original (1991) diagram (described in Chapter 10) looks like this:

It was Rosen who wrote the book on ‘anticipatory systems,’ but it has been widely recognized that anticipation is the key to guidance. Polanyi, for instance, remarked that our ‘whole set of faculties—our conceptions and skills, our perceptual framework and our drives—’ amount to ‘one comprehensive power of anticipation’ (Polanyi 1962, 103). Our meaning-cycle diagram is a way of picturing the form of that power, and the following passage from Polanyi could serve as a caption to it:

It was Rosen who wrote the book on ‘anticipatory systems,’ but it has been widely recognized that anticipation is the key to guidance. Polanyi, for instance, remarked that our ‘whole set of faculties—our conceptions and skills, our perceptual framework and our drives—’ amount to ‘one comprehensive power of anticipation’ (Polanyi 1962, 103). Our meaning-cycle diagram is a way of picturing the form of that power, and the following passage from Polanyi could serve as a caption to it:

Why do we entrust the life and guidance of our thoughts to our conceptions? Because we believe that their manifest rationality is due to their being in contact with domains of reality, of which they have grasped one aspect. This is why the Pygmalion at work in us when we shape a conception is ever prepared to seek guidance from his own creation; and yet, in reliance on his contact with reality, is ready to re-shape his creation, even while he accepts its guidance. We grant authority over ourselves to the conceptions which we have accepted, because we acknowledge them as intimations—derived from the contact we make through them with reality—of an indefinite sequence of novel future occasions, which we may hope to master by developing these conceptions further, relying on our own judgment in its continued contact with reality. The paradox of self-set standards is re-cast here into that of our subjective self-confidence in claiming to recognize an objective reality.

— Polanyi (1962, 104)

According to Howard Pattee (personal communication), Rosen first developed this diagram as a graphical representation of Heinrich Hertz’s description of the modeling process. (Pattee was working with Rosen at the Center for Theoretical Biology at Buffalo in the early 1970s, ‘when he was developing the ideas in Anticipatory Systems where his modeling diagram first appears.’) Hertz described the modeling process as follows:

We form for ourselves images or symbols of external objects; and the form which we give them is such that the logically necessary (denknotwendigen) consequents of the images in thought are always the images of the necessary natural (naturnotwendigen) consequents of the thing pictured.

For our purpose it is not necessary that they [images] should be in conformity with the things in any other respect whatever. As a matter of fact, we do not know, nor have we any means of knowing, whether our conception of things are in conformity with them in any other than this one fundamental respect.

— Hertz, The Principles of Mechanics, 1-2 (New York: Dover, 1984; original German edition, Prinzipien Mechanik, 1894)

This confirms Einstein’s point that the ‘natural system’ we are modeling is unknowable, in the sense that its inner workings are not directly observable. As modelers, we make an ‘epistemic cut’ (Pattee) between image and reality. The correspondence which defines the modeling relation as such is between the observed “behavior” of the “real” system (arrow #1, ‘causality’) and the ‘logically necessary consequents of the images in thought’ (arrow #3, ‘inference’).

This brings out a crucial point which is not clearly represented in the diagram: that any relevant act of observation takes time. In fact, every ‘observation’ or ‘measurement’ in science must consist of (at least) two measurements: one of the initial conditions, and another (some time later) after the system has ‘behaved’ in the situation we have chosen to focus on. What we call ‘the measurement’ is really the difference between these two measurements (even if it is zero because the system has not changed within the time frame). This is what Bateson calls ‘news of a difference’ (and Rosen calls ‘encoding’ – arrow #2). A theoretical model ‘works’ when that difference corresponds to some specific difference between states of the theoretical image, some aspect of the model’s dynamics.

Pattee adds that the diagram ‘also does not make clear that in a biological system the consequent of the model can be used to control its own state. The genetic description is a kind of model that exercises this kind of control of its own synthesis. This dependence of life on models or descriptions is what motivates the field of biosemiotics.’