If the great ocean thought it was full enough, the hundred rivers would flow backward.

— Dogen, Eihei Koroku 3.242 (Leighton and Okumura 2004, 240)

Author: gnox

Wholly

The Way of heaven is impartial.

Daodejing 79

Was there death before life?

Eternal life is the kind of life that includes death.

— Thich Nhat Hanh (1995, 143)

Thinking it through

Questings

Science is a communal quest for truth, religion a quest for true community.

Mourning the passing of morning

Comeday morm and O, you’re vine! Sendday’s eve and ah, you’re vinegar!

riverrun

Only in the stream of thought and life do words have meaning.

— Wittgenstein (1968, #173)

EarthTypes

Some time ago I included here a couple of quotes from David Grinspoon’s book Earth in Human Hands: Shaping Our Planet’s Future. Since then it’s become even more obvious that we (humans) are faced with the ‘fundamental Anthropocene dilemma … that we have achieved global impact but have no mechanisms for global self-control’ (Grinspoon). Is global self-control even possible for us? Can we even manage to compensate for some of the damage we’ve already done? What would it take to achieve that?

I think humanity as a whole would have to start thinking like a planet, becoming an instrument by which planet Earth can achieve a measure of its own self-control. This means learning to recognize the patterns which govern the life of the planet, and conforming the habits of our species to the habits of nature.

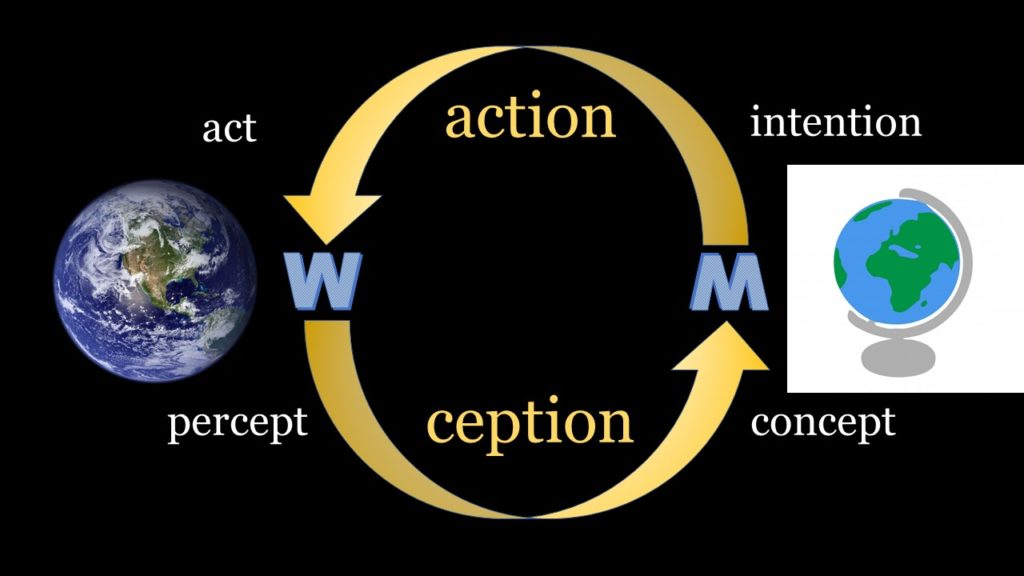

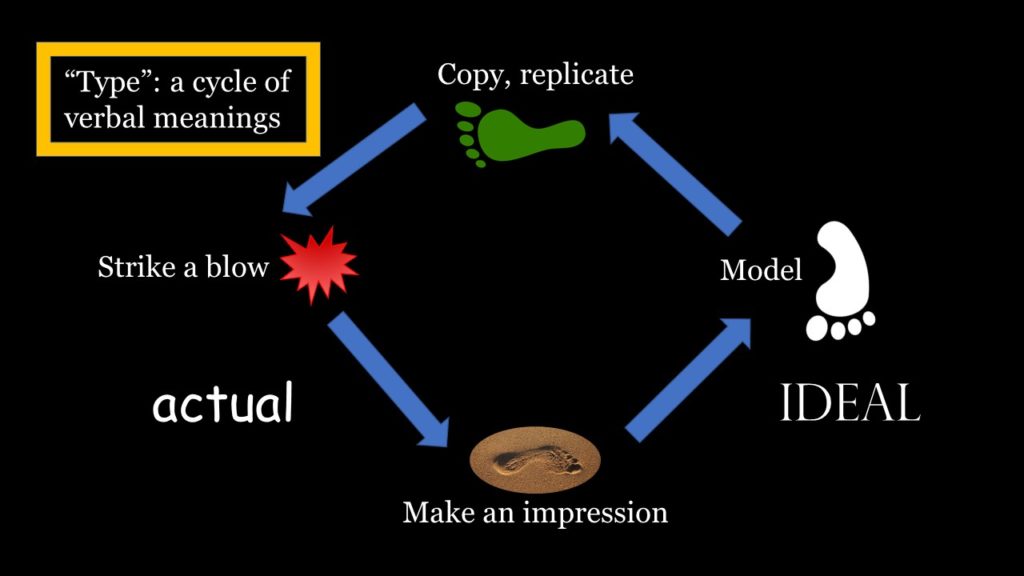

Like Gregory Bateson’s Mind and Nature (1979), Turning Signs is an attempt to delineate some of the ‘patterns that connect’ our thoughts with those of Nature – or of the Creator, the animating spirit of the universe. One of those patterns I call the ‘meaning cycle’. Sometimes the evolution of meaning of a single word follows this pattern. Take the word type. (For a concise view of its etymology, see the Online Etymological Dictionary.)

The ancient Greek word τύπος, in its earliest uses, referred to a “blow,” such as a sword against a shield. Later it referred to the dent or impression made by such a blow, or an imprint such as a footprint. Plato used it in reference to a mark on something, such as a letter written on a page. It could also refer to “anything wrought of metal or stone,” or more generally, a “figure, image or statue” (LSG) – a definite or static form made on or in some relatively permanent medium. Still more generally, it could mean the “general form or character of a thing” (LSG). These later senses migrated to Latin typus: “figure, image, form, kind.”

Already there is an ambiguity here, which we also find in English uses of the word. Most of us would agree that a bird is a type of animal. In other words, we recognize the class of animals as a very broad one which includes among its subclasses one called birds; but we also recognize that there are many subclasses or types of birds. So there is a hierarchy of generality, and animal is a more general term than bird. Yet bird is still a general term: it applies to all existing birds (as well as imaginary ones). As a type, or “form”, bird does not exist. That type is real, because it is really true to say that all existing birds are birds and not something else. There is a real connection between the existing individual being and the real form we call bird. But there is a crucial difference between the reality of types and the reality of existing things. This difference can create ambiguity whenever we use a general term.

Now suppose I ask you to imagine or visualize a bird. The image that comes to mind will probably (though vaguely) resemble whatever species of birds are most common in your everyday environment; and probably it will not resemble an ostrich or a penguin. We don’t think of these as typical birds, although they certainly belong to that biological class. Your concept of bird, then, is not an exact location in meaning space but a region with a centre and a periphery – both vaguely defined, but some birds appear closer to the centre than others. So your image (or “impression”) of a typical bird is more specific than the class of birds.

In the Oxford English Dictionary, the first meaning given under type is ‘that by which something is symbolized or figured; a symbol, emblem.’ In 19th-century English, the word “type” often referred to a specific image which seemed typical of something, or an individual specimen belonging to a class which served as a “model” for the whole class.

For a more visual presentation of all this, I’ve created a slideshow which you can view as a PDF here. But to continue verbally with the evolution of “type”:

In the early 18th century, type came into use for blocks of metal or wood with letters or characters carved on their faces for use in the printing process. So the meaning had moved from the striking of a blow to the impression made by the blow to the thing that made the impression, on paper or some other material. If you’re old enough to have used a typewriter, you remember using a keyboard to strike blows on paper and print letters on it. Nowadays keyboarding makes letterforms on a screen, but we still call those forms “typefaces” or “fonts,” both terms that originated in the printing process.

In an 1843 book on logic, John Stuart Mill wrote that

when we see a creature resembling an animal, we compare it with our general conception of an animal; and if it agrees with that general conception, we include it in the class. The conception becomes the type of comparison.

Since then, most uses of the word type have become pretty much synonymous with “kind” or “class,” and we no longer use it in reference to a typical but existing member of the class. We can no longer say that a robin is “the type” of all birds, although we can say that a robin is a prototypical example of the concept bird. So “type” now refers to a general rather than a specific “something.”

A common noun or adjective is always general to some degree, meaning that it can be applied to a range of individuals (who may differ in other respects but share the named character). In that sense every common noun is the name of a type. But here again there is ambiguity, because a general sign may be used collectively (referring to the type or class as a whole), or distributively (so that it refers to every individual of that type).

Charles S. Peirce used the word ‘type’ in most of the senses above, but he also adapted it for use as a technical term in semiotics for a different kind of generality. Here is his explanation (also given in Chapter 2 of Turning Signs):

A common mode of estimating the amount of matter in a MS. or printed book is to count the number of words. There will ordinarily be about twenty the’s on a page, and of course they count as twenty words. In another sense of the word “word,” however, there is but one word “the” in the English language; and it is impossible that this word should lie visibly on a page or be heard in any voice, for the reason that it is not a Single thing or Single event. It does not exist; it only determines things that do exist. Such a definitely significant Form, I propose to term a Type. A Single event which happens once and whose identity is limited to that one happening or a Single object or thing which is in some single place at any one instant of time, such event or thing being significant only as occurring just when and where it does, such as this or that word on a single line of a single page of a single copy of a book, I will venture to call a Token.

— Peirce, CP 4.537 (1906)

By clearly distinguishing it from a Token, which is an existing thing or actual event, Peirce brought another dimension of generality to the meaning of the word Type. It is not only a class-name but ‘a definitely significant Form’ which does not exist as an individual, or even as a singular collection, but ‘determines things that do exist.’ Taking his example of the word “the,” each existing imprint or Token of that word on a printed page is determined by its Type to take the visible form which makes it an instance of that significant Form. A Type which can really determine things that do exist even though it does not exist is another kind of reality. If we can understand how Types determine Tokens, we can clearly see that there is more to reality than existence.

Applying this to human language, we can say with Wittgenstein that what makes the Form of a Type significant is its use in the language. For instance, the language-user’s syntactic habits may determine that the Form is required as part of a given statement; then another semiotic habit determines what sound the speaker will produce at that point in her utterance – or yet another habit which associates that Form with certain visible shapes on the printed page determines what will appear in that part of the printed sentence. The shapes of the letters will be still more precisely determined by the choice of font or typeface in which the text is printed. But the word, as far as its meaning is concerned, is the same word regardless of typeface, and likewise regardless of whether it is printed or spoken. In other words, that word is a real Type in Peirce’s exact sense of the word.

The habits which govern our acts of meaning are partly artificial and partly natural. The natural habits of meaning are also habits of the Earth, embodied in the actual behavior of earthlings like us. Those are the habits which make it possible to learn from experience, while our conventional linguistic habits make it possible to symbolize what we learn, so that we can take some control of our own habits. If we can somehow synchronize our collective habits with the habits of the Earth (or of Gaia, if you like), then eventually the Earth can use us to develop a measure of self-control, to better determine its own future. This is the challenge of the Anthropocene. Turning Signs is one attempt to show how such a challenge might be met at the the individual, cultural, ecological and planetary levels. It all depends on recognizing the Types, the “patterns that connect” reality with imagination, as the habits of the Earth.

Specially general

It is of the very essence of thought and purpose that it should be special, just as truly as it is of the essence of either that it should be general.

This statement by Charles S. Peirce is from his Lowell Lecture 8 of 1903 – and more specifically, from a little meditation on ethics and esthetics within that lecture:

The question is what theories and conceptions we ought to entertain. Now the word “ought” has no meaning except relatively to an end. That ought to be done which is conducive to a certain end. The inquiry therefore should begin with searching for the end of thinking. What do we think for? What is the physiological function of thought? If we say it is action, we must mean the government of action to some end. To what end? It must be something good or admirable, regardless of any ulterior reason. This can only be the esthetically good. But what is esthetically good? Perhaps we may say the full expression of an idea? Thought, however, is in itself essentially of the nature of a sign. But a sign is not a sign unless it translates itself into another sign in which it is more fully developed. Thought requires achievement for its own development, and without this development it is nothing. Thought must live and grow in incessant new and higher translations, or it proves itself not to be genuine thought.

But the mind loses itself in such general questions and seems to be floating in a limitless vacuity. It is of the very essence of thought and purpose that it should be special, just as truly as it is of the essence of either that it should be general. Some writers have called the circle beautiful: but it has no features: it is expressionless. No curve can be very beautiful, because the thought it embodies is too meagre. But as curves go, bicyclic quartics are as a matter of fact pleasing; and I think the reason is that they have something of the perfect regularity of the circle, with a continuity of a kind which developes special features. Hogarth’s line of beauty

is the simplest case of a special feature, a singularity, as it is called by geometers, which the law of the continuity itself engenders, without destroying the continuity. All this may seem to be very foreign to logic, and perhaps it is so. Yet it illustrates the point that the valuable idea must be eminently fruitful in special applications, while at the same time it is always growing to wider and wider alliances.

This appears to be one more example of Peirce’s recurring idea that ‘symbols grow.’ It also serves as an application of the creative tension (or tention) which is found to be a core attibute of both life and semiosis in Turning Signs. In this case, the tension is between the generality and the specificity of thought.

True science

Genuine science is the expression of a ‘will to learn’ driven by curiosity about how Nature works, and not by curiosity about how the newly gained knowledge will serve our practical purposes as presently conceived.

Some would say that inquiry is not “pragmatic” if we have no idea of the practical applications that might result from it.

Now to this, to be sure, one can reply that no curiosity is more disadvantageous to the expansion of our knowledge than that which would always know its utility in advance, before one has entered into the investigations, and before one could have the least concept of this utility even if it were placed before one’s eyes.

— Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, B296-7

The deeper the inquiry, the more it may cause us to revise our concept of “utility.” As Peirce put it (CP 1.76), ‘True science is distinctively the study of useless things.’