Toties testies quoties questies. The war is in words and the wood is the world. Maply me, willowy we, hickory he and yew yourselves. Continue reading How Forests Think

Wild science

A pretty wild play of the imagination is, it cannot be doubted, an inevitable and probably even a useful prelude to science proper.

— Peirce, CP 1.235 (1902)

The Life of Jesus

No Evangelist has the slightest interest in writing a biography of Jesus. The Jesus about whom a biography can be written is dead and gone, and survives only as Antichrist. The Evangelists tell us not how Christ came, but how he comes: they are concerned not with a vanished past but with the imagination’s ‘Eternal Now.’ The timid will protest that we are here in danger of dissolving the reality of Christianity into a vaporous allegory; Blake’s answer is that the core of reality is mental and present, not physical and past. Past events do not necessarily dissolve in time, but their existence in the eternal present depends on imaginative recreation.

— Northrop Frye (1947, 343)

On time

Presence takes time, and time is the continuity of presence.

Remembering is the re-presentation of past forms. Embodiment of forms is actual (present) practice. Imagination is the practice of future forms.

Authentic art expresses the truth of the time, while science aims at a final truth which can never be fully expressed.

Vacation

Vacation: leaving work, leaving home; holiday, holy day; vacancy, emptiness.

An obsolete meaning given in the Oxford English Dictionary: ‘Leisure for, or devoted to, some special purpose; hence, occupation, business.’ Vocation?

The English word was used in 1450 to translate the Latin phrase Dei vacationem: ‘Put the vacacion of god before all other thinges.’

Reading through

Three symbols: the Word, ourselves, the world. We are here to recognize turning signs as such, to recognize one another, to recognize nature; and for the recreation of all three. To read any one truly is to read it through the other two.

Manifold appearances and myriad forms, and all spoken words, each should be turned and returned to oneself and made to turn freely.

— Pai Chang, cited in Blue Cliff Record Case 39 (Cleary and Cleary 1977, 241)

The use of the useless

Everybody knows the use of the useful, but nobody knows the use of the useless!

— Chuangtse 4

In the late 20th century it was customary to divide the functions of the mass media into information and entertainment (with ‘infotainment’ as a sort of bastard child of the two). The information media were supposed to feed us facts, while the entertainment media fed us fictions and artistic performances – which were “recreational,” meaning “of no practical value” (other than profits for its owners and sponsors).

Our use of the terms ‘recreate’ and ‘recreation’ in connection with turning signs is quite different, and we might ask how it relates to “entertainment.” We all need diversion to clean out the clutter of habits that cling to daily life. Or rather, we need ways to shuffle off the coil of distractions that cling to us. Entertainment is one way of turning ourselves over to new patterns, new messages. It can even improve our practice just by interrupting it. “The pause that refreshes” is a phenomenon detectable even down to the neuronal level (Austin 1998, Chapter 83). At the basic level, a pause of the right length in any routine or procedure will generally refresh the routine. (This is one of the uses of the useless.) But entertainment can also be used to “kill time,” or to drown out messages not wanted by the owners of the mainstream media. This has turned out to be a more effective means of ‘thought control’ than overt censorship (Herman and Chomsky 1988).

Our use of the terms ‘recreate’ and ‘recreation’ in connection with turning signs is quite different, and we might ask how it relates to “entertainment.” We all need diversion to clean out the clutter of habits that cling to daily life. Or rather, we need ways to shuffle off the coil of distractions that cling to us. Entertainment is one way of turning ourselves over to new patterns, new messages. It can even improve our practice just by interrupting it. “The pause that refreshes” is a phenomenon detectable even down to the neuronal level (Austin 1998, Chapter 83). At the basic level, a pause of the right length in any routine or procedure will generally refresh the routine. (This is one of the uses of the useless.) But entertainment can also be used to “kill time,” or to drown out messages not wanted by the owners of the mainstream media. This has turned out to be a more effective means of ‘thought control’ than overt censorship (Herman and Chomsky 1988).

Another word for it is amusement, from the old French word amuser, meaning to cause someone to muser, ‘to stare stupidly’ (OED). The usual sense of the word in the 17th-18th century was ‘to divert the attention of anyone from the facts at issue; to beguile, delude, cheat, deceive … to divert in order to gain or waste time.’

As if you could kill time without injuring eternity.

— Thoreau, Walden

Thoreau’s contemporary Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote in 1835 of the ‘peculiar weariness and depression of spirits which is felt after a day wasted in turning over a magazine or other light miscellany, different from the state of the mind after severe study; because there has been no excitement, no difficulties to be overcome, but the spirits have evaporated insensibly’ (American Notebooks, 11).

After a century and a half of technological development had vastly increased the addictive power of entertainment, Gregory Bateson took this observation a bit further:

… in art, as opposed to entertainment, it is always uphill in a certain sense, so the effort precedes the reward rather than the reward being spooned out. One of the things that is important in depression is not to get caught in the notion that entertainment will relieve it. It will, you know, briefly, but it will not banish it. As reassurance is the food of anxiety, so entertainment is the food of depression.

— Bateson and Bateson (1987, 132)

Chögyam Trungpa said much the same about what he called ‘the art of the setting sun’:

We have a lot of examples of setting-sun art. Some of them are based on the principle of entertainment. Since you feel so uncheerful and solemn, you try to create artificial humor, manufactured wit. But that tends to bring a tremendous sense of depression, actually. There might be a comic relief effect for a few seconds, but apart from that there is a constant black cloud, the black air of tormenting depression. As a consequence, if you are rich, you try to spend more money to cheer yourself up – but you find that the more you do, the less it helps. There is no respect for life in the setting-sun world.

— Trungpa (1999, 29)

Life-respecting art, on the other hand (Trungpa’s ‘art of the Great Eastern Sun’) furnishes us with experiences that renew and reshape the patterns of our perceptions and conceptions. So the question to ask of every recreational experience is: Does it make a difference? Is it transformative or addictive? We ask this of the experience of reading the artistic sign, which depends on the interbeing of reader, text and context – although we sometimes pretend that the text is responsible, as when we say This story is interesting or This story is boring. Any text, regardless of its origin, can become a turning sign if it is consecrated in the act of reading to the transformation and recreation of life. The spiritual life is the one which takes re-creation seriously, and takes the serious joyfully.

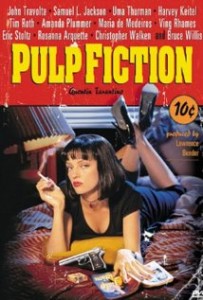

When you read pulp fiction, or pulp fact such as ‘the news’, you expect it all to fit comfortably into the framework of your familiar description of the world – the usual disasters, crimes, conflicts, maneuvers, gestures on the public stage and other external events. In other words you don’t expect it to call for deep attention or to transform your life; that is not what ‘entertainment’ is for. But something may reach you through these media nevertheless, precisely because you are uncritically and unintentionally open to it while you submit to being entertained. You never know where the next revelation may come from, and it may be all the more effective for coming when you least expect it. It’s just a matter of shifting into deep reading mode when you hear the wake-up call.