Of passing many sentences

and making many periods

there is no point.

Author: gnox

Gut feelings

In animals with brains, it is primarily the brain’s map of the body that monitors (through the nervous system) the state of the various subsystems that keep the body functioning (Damasio 2010). Since the body’s well-being often requires responses to events in its environment, parts of it (eyes, ears, etc.) are specialized to bring us news of what’s going on out there. Thus the brain’s map of the body includes an indirect mapping of the environment, or rather of the body’s relations with relevant aspects of it.

Turning Signs, Chapter 3

But the most direct mapping of the body, and the primal index of its well-being (or ill-being), comes to consciousness in the form of visceral feelings – gut feelings in the true sense of the term. These arise from inside the body, not through the sensors in the eyes, ears, nose or skin but through the ‘enteric nervous system – the complicated mesh of nerves that is present in our gastrointestinal tracts’ (Damasio 2018, 60). In evolutionary terms, this is the oldest part of the nervous system, and the most intimately connected with the body it serves and regulates. Yet the digestive system is also inhabited by far more primal beings, single-cell life forms that vastly outnumber the human cells with which they live in symbiotic partnership.

In the human gut alone, there are usually around 100 trillion bacteria, while in one entire human being there are only about 10 trillion cells, counting all types.

— Antonio Damasio, The Strange Order of Things (2018), 53

These bacterial cells are inside us but not of us in the way that the 10 trillion cells ‘in one human being’ are. However, all these lives share one basic tendency called homeostasis: they self-regulate to maintain a chemical balance within their bodies that is conducive to their well-being and flourishing. That tendency, much older than brains or nervous systems, is the core of whatever intelligence any life form has.

Bacteria are very intelligent creatures; that is the only way of saying it, even if their intelligence is not being guided by a mind with feelings and intentions and a conscious point of view. They can sense the conditions of their environment and react in ways advantageous to the continuation of their lives. Those reactions include elaborate social behaviors. They can communicate among themselves – no words, it is true, but the molecules with which they signal speak volumes. The computations they perform permit them to assess their situation and, accordingly, afford to live independently or gather together if need be. There is no nervous system inside these single-celled organisms and no mind in the sense that we have. Yet they have varieties of perception, memory, communication, and social governance. The functional operations that support all this “intelligence without a brain or mind” rely on chemical and electrical networks of the sort nervous systems eventually came to possess, advance, and explore later in evolution.

— Damasio 2018, 53-4

Bodyminds with brains carry on the ancient homeostatic tradition by monitoring the state of the body’s interior, and representing that state in the form of feelings. Interoception is deeper than perception; our feelings about things and events around us are rooted in their relations to the state of the body, as represented to the mind by the images we call “feelings.”

Feelings are the mental expressions of homeostasis, while homeostasis, acting under the cover of feeling, is the functional thread that links early life-forms to the extraordinary partnership of bodies and nervous systems. That partnership is responsible for the emergence of conscious, feeling minds that are, in turn, responsible for what is most distinctive about humanity: cultures and civilizations. Feelings are at the center of the book, but they draw their powers from homeostasis.

— Damasio 2018, 6

Damasio’s book proceeds to explain how feelings, ‘the most fundamental of mental states,’ give rise to subjectivity, consciousness, imagination, reasoning and cultural invention.

When feelings, which describe the inner state of life now, are “placed” or even “located” within the current perspective of the whole organism, subjectivity emerges. And from there on, the events that surround us, the events in which we participate, and the memories we recall are given a novel possibility: they can actually matter to us; they can affect the course of our lives.

— Damasio 2018, 158

So, by Damasio’s account at least, gut feelings not only matter, they are the primal source of meaning for beings like us.

Organic

Say what?

When your felt sense works its way into words, the act of meaning collides and colludes with the limits of language to determine what you say.

for Sake

And he said to all, “If any man would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow me. For whoever would save his life [psyche] will lose it; but whosoever shall lose his life [psyche] for my sake [ἕνεκεν ἐμοῦ], he will save it. For what does it profit a man if he gains the whole world and loses or forfeits himself?

— Luke 9:23-5 (RSV)

Is his sake like your sake, or my sake, or God’s sake? What is a sake anyway? Are there any synonyms for that word? Where did it come from?

It came into English originally “for God’s sake,” according to the online etymological dictionary (consulted 25 March 2018):

{sake (n.1): “purpose,” Old English sacu “a cause at law, crime, dispute, guilt,” from Proto-Germanic *sako “affair, thing, charge, accusation” (source also of Old Norse sök “charge, lawsuit, effect, cause,” Old Frisian seke “strife, dispute, matter, thing,” Dutch zaak “lawsuit, cause, sake, thing,” German Sache “thing, matter, affair, cause”), from PIE root *sag- “to investigate, seek out” (source also of Old English secan, Gothic sokjan “to seek;” see seek).

Much of the word’s original meaning has been taken over by case (n.1), cause (n.), and it survives largely in phrases for the sake of (early 13c.) and for _______’s sake (c. 1300, originally for God’s sake), both probably are from Norse, as these forms have not been found in Old English.}

So we trace it back to a Proto-Indo-European root *sag- (which, as the asterisk signifies, is our best guess at what the original prehistoric form would have been, working back from the actually attested forms).

Who is the one ‘for whose sake heaven and earth came into being’? Was or is the primal person a seeker for his sake? Is there a primal cause, or purpose, or crime? Who is trying this case?

The answer is always there, but people need the question to bring it out.

— Thomas Cleary (1995, 164)

Kingdom Come

we’re flying high on a wing and a prayer

I hope we know when we get there— Oysterband, ‘Wayfaring’

Now having been questioned by the Pharisees as to when the kingdom of God was coming, He answered them and said, “The kingdom of God is not coming with signs to be observed; nor will they say, ‘Look, here it is!’ or, ‘There it is!’ For behold, the kingdom of God is in your midst.”

— Luke 17:20-21

… or as the King James Version has it, “the kingdom of God is within you.” Its coming is unobservable, like the time you are living in. We cannot observe spacetime: we can only observe differences or changes in the current state of things. Can you direct your attention to the ground of your attention (and your intentions)?

In the Gospel of Thomas, the question was put to Jesus by his disciples:

His disciples said to him, “When will the kingdom come?”

“It will not come by watching for it. It will not be said, ‘Look, here it is,’ or ‘Look, there it is.’ Rather, the Father’s kingdom is spread out upon the earth, and people do not see it.”logion 113 (NHS)

At another time they asked him a very similar – or is it the same? – question:

His disciples said to him, “When will the rest for the dead take place, and when will the new world come?”

He said to them, “What you look for has come, but you do not know it.”Gospel of Thomas 52 (NHS)

In Greek/Coptic, the word for ‘rest’ here is anapausis. Some say this is a mistake for anastasis, which means ‘resurrection’ – another event connected to the coming of the Kingdom and the new world. But perhaps ‘rest’ is just the other side of the coin of ‘resurrection’ – both beneath our knowledge, like the water underground.

Die Aufgabe

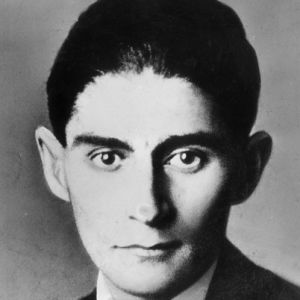

Du bist die Aufgabe. Kein Schüler weit und breit.

This is one of a series of aphorisms written by Franz Kafka in 1917-18. An Aufgabe is an assignment given by a teacher as a problem to be solved by a student. But in this case

You are the problem and there is no student available (or able?) to solve you.

Who made you a problem, a task to be done, a mission to be accomplished?

Can a problem solve itself?

You are unique

— just like everybody else.

Stealing into simplicity

Broadcast, O mullāh,

your merciful call to prayer—

you yourself are a mosque

with ten doors. Make your mind your Mecca,

your body, the Ka’aba—

your Self itself

is the Supreme Master. In the name of Allāh, sacrifice

your anger, error, impurity—

chew up your senses,

become a patient man. The lord of the Hindus and Turks

is one and the same—

why become a mullāh,

why become a sheikh? Kabir says, brother,

I’ve gone crazy—

quietly, quietly, like a thief,

my mind has slipped into the simple state.— Kabir, from Weaver’s Songs, tr. Vinay Dharwadker. Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

Only?

What is now proved was once only imagined.

— William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, plate 8