The meanings of words in English can be described as ‘conventional,’ but in most cases no ‘convention’ was ever called where users of a word got together to decide what those words would express. Many users of the English language never chose to do so, because it was forced upon them along with the colonial rule of the British (or the American) Empire. But some have resisted colonization by consciously creating their own conventions, their own dialect of English.

One good example of such creative cultural transformation is the “patois” of the Rastafarians.

One good example of such creative cultural transformation is the “patois” of the Rastafarians.

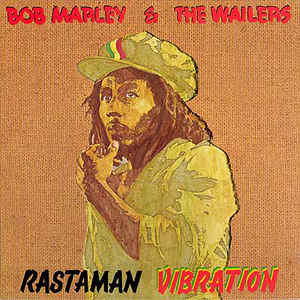

In the past half century, Rastafarian language found its way into globally popular culture through the spread of reggae music and the lyrics of artists such as Bob Marley. His ‘Redemption Song’ is one example:

Old pirates yes they rob I

Sold I to the merchant ships

Minutes after they took I

From the bottomless pit …

Standard English would call for “me,” or maybe “us,” instead of “I” here. But this repurposing of “I,” including the Rastafarian use of “I an’ I” for the first person pronoun, has a deep spiritual significance for this religion of ‘love and unity.’ It is part of what Marley calls the ‘I’n’I vibration’ in his song ‘Positive Vibration’, and is connected with the central figure of the religion, Haile Selassie I (Ras Tafari is another name for him.)

For many Rastas, the ‘I’ after Selassie is multivalent in its significance. Read as ‘first’, it points to his pre-existence from the beginning and to his preeminence as earth’s ‘rightful ruler’. Read as the first person singular pronoun ‘I’, which is generally how Rastas pronounce it, it becomes an indicator of Selassie’s divinity. From this understanding, Rastas extrapolate that ‘I’ represents the divine essence of humans. They then elaborated the philosophy of InI consciousness (‘Isciousness’) as the realization of one’s own divine identity.

— Edmonds, Ennis B.. Rastafari: A Very Short Introduction (p. 37). OUP Oxford. Kindle Edition.

For instance, to indicate the divinity of “Creation”, Rastas call it “Iration” instead.

In 1983, the year after Bob Marley’s death, Bob Dylan released a song titled ‘I and I’ (on the album Infidels). The chorus goes like this:

I and I

In creation where one’s nature neither honors nor forgives

I and I

One says to the other, no man sees my face and lives

One of the verses tells how it

Took a stranger to teach me, to look into justice’s beautiful face

And to see an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth

This song puts yet another spiritual spin on the Rastafarian expression. Or at least it seems that way to I and I. How about you and you?

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the impact of everyday words and phrases that we all use often and how they impact a person’s creativity, empowerment and place in society. So this chapter has given me so much more to think about: thank you.

Here is a preliminary go at ‘You and you’: It is a second person phrase and within the context of colonialized language signifies ‘other’. Such a rendering could be seen to classify and divide: it does not intend to unify. With ‘I n I’ the impact of ego is lessened so experience is equally valued. With ‘you and you’ it is ‘I’ – first person – who speaks the phrase, with ego leading, experience not equal.