The creature that wins against its environment destroys itself.

— Gregory Bateson (1972, 493)

Author: gnox

Perfect signature

Forget this moment and grow into the next. That is the only way.… So the point on each moment is to forget the point and extend your practice.

— S. Suzuki (2002, 18)

So why, pray, sign anything as long as every word, letter, penstroke, paperspace is a perfect signature of its own?

— Finnegans Wake, 115

Leave the letter that never begins to go, find the latter that ever comes to end, written in smoke and blurred by mist and signed of solitude, sealed at night.

— The Restored Finnegans Wake, 260

— Dream. On a nonday I sleep. I dreamt of a somday. On a wonday I shall wake.

— The Restored Finnegans Wake, 373

— As you sing it it’s a study. That letter selfpenned to one’s other, that neverperfect everplanned!

— This nonday diary, this allnights newseryreel.— The Restored Finnegans Wake, 380

Ring the bells that still can ring.

Forget your perfect offering.

There is a crack a crack in everything.

That’s how the light gets in.— Leonard Cohen, ‘Anthem’

Theory

In theory there is no difference between theory and practice; in practice there is.

Surdity

Let us swop hats and excheck a few strong verbs weak oach eather yapyazzard abast the blooty creeks.

— FW 16

Thus begins the conversation between Mutt and Jute in the early pages of Finnegans Wake. It continues rather like a dialogue of the deaf:

Jute.— Yutah!

Mutt.— Mukk’s pleasurad.

Jute.— Are you jeff?

Mutt.— Somehards.

Jute.— But you are not jeffmute?

Mutt.— Noho. Only an utterer.

Jute.— Whoa? Whoat is the mutter with you?

Mutt.— I became a stun a stummer.

Jute.— What a hauhauhauhaudibble thing, to be cause! How, Mutt?

Mutt.— Aput the buttle, surd.

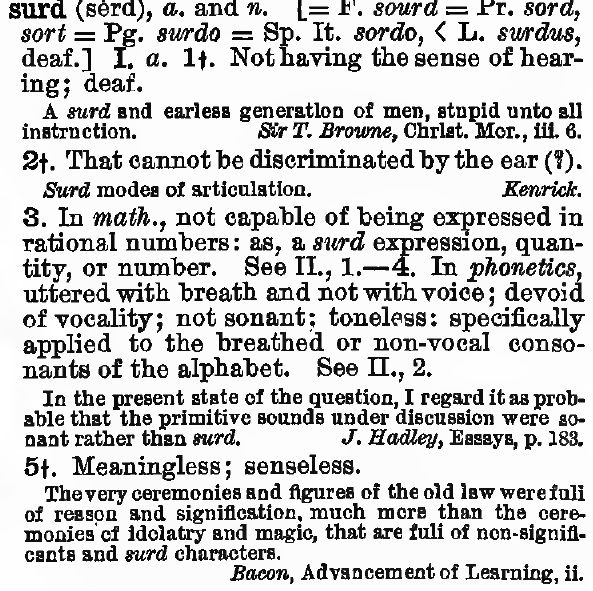

That last word is not often heard in everyday English, but it suits the story here, as the primal meaning of its Latin root surdus is “deaf.” But then the notion of “hard of hearing” slips over (by way of stuttering, stammering and muttering) into “hard to hear,” and thence to “unintelligible” or “irrational,” and thence to “meaningless.” This diversity was documented by C.S. Peirce in the Century Dictionary:

In his later work on logic as ‘the Basis of Pragmatism,’ Peirce used the word as a technical term applied to ‘the relation implied in duality,’ which ‘is essentially and purely a dyadic relation’ (EP2:382). A surd relation is the opposite of a dicible one. In less Latinate diction, you could say that a surd relation is “unsayable,” or perhaps “unreasonable.” It can be experienced but not really described.

For the only kind of relation which could be veritably described to a person who had no experience of it is a relation of reason. A relation of reason is not purely dyadic: it is a relation through a sign: that is why it is dicible. Consequently the relation involved in duality is not dicible, but surd …

EP2:382-3

Since all reasoning is in signs, a ‘relation of reason’ is triadic even if it seems to have only two correlates, two ‘subjects’ (like Mutt and Jute). It lacks the surdity of a ‘purely dyadic relation.’ But the only way our two ‘jeffmutes’ could enter into a purely dyadic relation would be to collide with each other, perhaps in a head-butting battle. The duality of their duel is clear enough ‘aput the buttle,’ but they do manage to swop hats and excheck a few verbs, thus making their relationship more triadic. If they both sound a bit “stunned,” maybe that’s just the effect of taking turns at the bottle.

Turning to genuine triadic relations, and thus to signs, we find that the Secondness of the dynamic relation between Sign and Object – or in communication, the duality between Utterer and Interpreter – must also be genuine, must be a ‘real’ relation, not a ‘relation of reason.’ As explained elsewhere, the element of Secondness or surdity must be involved in any honest attempt to understand, speak or hear the truth.

This may sound unsound or even absurd, but it is borne out by the twisted history of words themselves. If our language were entirely rational, for instance, the word absurd would mean “far from surd,” just as abnormal means “far from normal.” But in fact surd and absurd mean pretty much the same thing. Why? It’s hard to say, surd.

As Peirce remarked in the Century Dictionary, absurd is ‘a word of disputed origin’ – there is no dispute about what it actually means in everyday discourse, but a reasonable account of how it came to mean that has to choose between two possible significations of the prefix ab-. If it means “away from” (as in “absent” or “abnormal”), then combining it with the Latin root surd could not generate the usual meaning of absurd. Some say that the -surd part might come from a Sanskrit root that sounds similar but means “sound” (rather than “deaf”). Then absurd could have meant something like “inharmonious,” and thence “unsound” in the sense of “unreasonable.” The other side in the dispute say that the Latin and English surd is the root, but the prefix ab- acts as an ‘intensive’ rather than a negative (as it seems to do in “aboriginal”), thus making absurdity even more unreasonable or nonsensical than surdity.

The point is that, whether we can explain it or not, the common sense of the word absurd is “contrary to common sense” (CD), because that is how people actually use it. Likewise actual facts, no matter how well known, always carry a residue of unspeakable or inexplicable surdity. ‘Facts don’t do what I want them to,’ as Byrne and Eno put it. The element of Secondness in them keeps our knowledge real and our quest for Truth honest.

Buttle

One person’s distraction is another’s revelation – and vice versa.

Real economy

Here’s one iconic symbol we ought to be turning to. You can read all about it in Kate Raworth’s blog and book on Doughnut Economics. The doughnut is an icon well suited to “accounting for what really counts” (the slogan of gnusystems).

Economists and politicians, including our Prime Minister, are still chanting the old mantra of economic “growth” as if it were the panacea which would solve all our problems and improve all our lives. But as soon as you ask what the purpose of an economic system is, as Kate Raworth did, you see that growth does not always serve that purpose, and sometimes works against it. And what’s more, the politicians who have relied on this mantra to manufacture consent for their programs have used it mainly to increase the gap between rich and poor.

Kate’s latest blog post presents the choice between economic “paradigms” in its simplest terms. The old one is based on the belief that people are greedy, insatiable and competitive. The new one is based on the belief that “people are greedy and generous, competitive and collaborative – and it’s possible to nurture human nature.” You’re invited to decide which belief you want to live by.

Startlings

Only that day dawns to which we are awake. There is more day to dawn. The sun is but a morning star.

— Thoreau, Walden, chp. 18

We still and always want waking.

— Annie Dillard, The Writing Life (1989, 593)

And then. Be old. The next thing is. We are once amore as babes awondering in a wold made fresh where with the hen in the storyaboot we start from scratch.

— Finnegans Wake, 336

It is only by taking fresh looks at situations thought already to be understood that we come up with truly insightful and creative visions. The ability to reperceive, in short, is at the crux of creativity.

— Hofstadter/FARG (1995, 308)

Willy-nilly

A person can do what he wants, but not want what he wants. Der Mensch kann tun was er will; er kann aber nicht wollen was er will.

— Schopenhauer, On The Freedom Of The Will (1839)

In the last of his 1903 Harvard lectures, Peirce pointed out that ‘self-control of any kind is purely inhibitory. It originates nothing’ (EP2:233). What then is the ground of the guidance system governing the practice of a bodymind? Ultimately, says Peirce, ‘it must come from the uncontrolled part of the mind, because a series of controlled acts must have a first’ (EP2:233).

The same goes for acts of meaning. All of our reasoning, including the very form of the process, originates in what is “given” to us in perceptual judgments. Every such judgment is ‘the result of a process’ which is ‘not controllable and therefore not fully conscious’ (EP2:227). Consciousness takes up the task of controlling the process, domesticating it, harnessing a ‘logical energy’ which is originally wild. In its Firstness it is spontaneous and free, and yet the very origin of self-control. Logic as the ethic of inquiry is the heart of self-control in the use of symbols, but is grounded in a process continuous with direct perception, even with creation.

A consciousness for which the world is “self-evident,” that finds the world “already constituted” and present even within consciousness itself, absolutely chooses neither its being nor its manner of being.

What then is freedom? To be born is to be simultaneously born of the world and to be born into the world. The world is always already constituted, but also never completely constituted. In the first relation we are solicited, in the second we are open to an infinity of possibilities.…We choose our world and the world chooses us.

— Merleau-Ponty (1945, 527)

There’s a split in the infinitive from to have to have been to will be.

— Finnegans Wake, 271

Starting point

It’s difficult to see the picture when you are inside the frame.

— anon

So long as I keep before me the ideal of an absolute observer, of knowledge in the absence of any viewpoint, I can only see my situation as being a source of error. But once I have acknowledged that through it I am geared to all actions and all knowledge that are meaningful to me, and that it is gradually filled with everything that may be for me, then my contact with the social in the finitude of my situation is revealed to me as the starting point of all truth, including that of science and, since we have some idea of the truth, since we are inside truth and cannot get outside it, all that I can do is define a truth within the situation.

— Merleau-Ponty, quoted in Prigogine and Stengers 1984, 299

To seek Buddhahood apart from living beings is like seeking echoes by silencing sounds.

— Layman Hsiang (Cleary 1999, 93)

Seeking enlightenment apart from the world

Is like looking for horns on a hare.— Hui-neng (Cleary 1998, 23)

Selfies

Some spiritual traditions regard the ultimate reality as the Self. Others regard the Self as an illusion. The correctness of each view is self-evident.

This sentence contradicts itself—or rather—well, no, actually it doesn’t!

— Douglas Hofstadter (1985, 7)