A path is made by people walking on it; a path discovers itself by crossing with other paths.

Reader, I beg you will think this matter out for yourself, and then you can see — I wish I could — whether your independently formed opinion does not fall in with mine.

— Peirce, CP 4.540 (‘Prolegomena’, 1906)

Once a person has escaped the cage of his own opinions by entering into the quest for truth, even the internal monologue, the stream of consciousness expressed as a train of thought, can be a dialogue, or even a dialog (for the difference, see the obverse of this chapter). What counts is the sense of mission, the spirit of inquiry. The logic of this, as Peirce saw it, is that each thought is addressed by the self you are now to the self you will be momentarily: past self addresses future self through present semiosis, and the former future self proceeds to test the received idea. A philosophical writer like Peirce will typically test an idea in this way, sometimes for years, before she considers it worthy to launch into the great conversation for further testing.

The appearance of monologue, then, can be deceptive. The difference between an ordinary conversation and the reading of a text like this one is mostly a matter of medium (spoken, written, printed, electronic, etc.) and of time scale. The great conversation among authors is simply a macro-dialog, in which each partner can take years, or a lifetime, to consider and deliver his reply to what’s been said before. Since a partner does not have to wait her turn, and can reply to any number of prior texts all at once, this conversation is ‘wired’ in parallel rather than series – it’s a network rather than a train of thought. Even readers who never write are involved in this conversation, to the extent that their reading makes a difference in how they live their lives. True, the reader/author relationship is not symmetrical in ‘real time’ like the partnership in a face-to face conversation, because the text of a book does not change in response to the reader’s contribution – but the meaning certainly does. A book on the shelf means nothing at all. Don’t think that the meaning is all in the text, or all in your mind. The meaning is in the relationship, the intimate space, between you and me. Regardless of scale or medium, dialog is always talking through together.

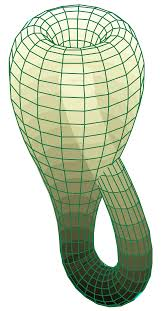

One of the subjects that came in for some discussion this week was the overall structure of Turning Signs, with its Obverse and Reverse sides. Chapter One says that it ‘resembles a Klein bottle,’ but that may need some explanation. Fortunately i discovered

One of the subjects that came in for some discussion this week was the overall structure of Turning Signs, with its Obverse and Reverse sides. Chapter One says that it ‘resembles a Klein bottle,’ but that may need some explanation. Fortunately i discovered