Eugene Gendlin wrote that ‘the living body is an interactive process with its environment and situation’ (Hendricks 2004, 8). Its life is its withness.

We could say this of the whole biosphere, as suggested by John Palka in his blog post Is Earth Alive?, which reconsiders the “Gaia hypothesis” originally proposed by Lynn Margulis and James Lovelock. John Palka, “a neuroscientist who loves plants and ponders big questions,” quotes from a recent book by planetary scientist David Grinspoon:

Margulis and Lovelock proposed that the drama of life does not unfold on the stage of a dead Earth, but, that, rather, the stage itself is animated, part of a larger living entity, Gaia, composed of the biosphere together with the “nonliving” components that shape, respond to, and cycle through the biota of the Earth. Yes, life adapts to environmental change, shaping itself through natural selection. Yet life also pushes back and changes the environment, alters the planet. This is now as obvious as the air you are breathing, which has been oxygenated by life. So evolution is not a series of adaptations to inanimate events, but a system of feedbacks, an exchange. Life has not simply molded itself to the shifting contours of a dynamic Earth. Rather, life and Earth have shaped each other as they’ve coevolved.

Palka’s article gives several specific examples of life changing its environment on this planet. Grinspoon’s book, Earth in Human Hands, is about the “Anthropocene epoch,” in which “the net activity of humans has become a powerful agent of geological change.” Here’s another sample from it:

I think our fundamental Anthropocene dilemma is that we have achieved global impact but have no mechanisms for global self-control. So, to the (debatable) extent that we are like some kind of global organism, we are still a pretty clumsy one, crashing around with little situational awareness, operating on a scale larger than our perceptions or motor skills. However, we can also see our civilization, such as it is, becoming knitted together by trade, by satellite, by travel, and instantaneous communications, into some kind of new global whole—one that is as yet conflicted and incoherent, but which is arguably just beginning to perceive and act in its own self-interest.

— Grinspoon, David (2016-12-06). Earth in Human Hands: Shaping Our Planet’s Future (Kindle Locations 158-163). Grand Central Publishing. Kindle Edition.

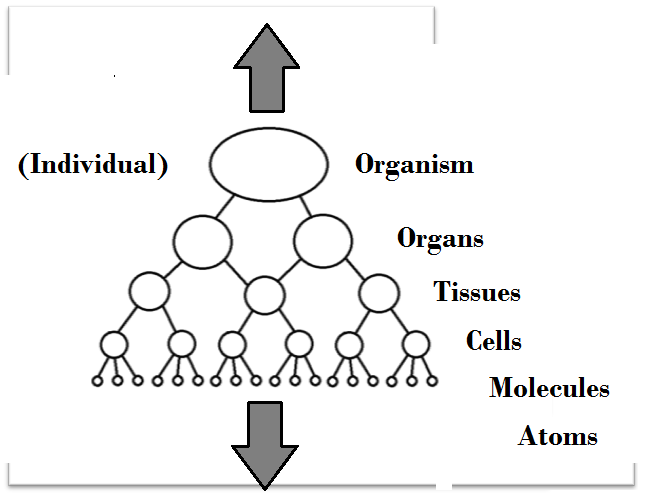

Yet each cell has its own life or identity, constituted by still smaller-scale molecular interactions; and we ourselves form the substrate of larger-scale entities, such as communities and ecosystems. At that level, the dialogue of which this book is a minute part may constitute the thoughts of a “global brain,” expressed in a vast language we humans can only imagine by analogy with human languages. But its context is beyond our comprehension. Is there a being for whom “

Yet each cell has its own life or identity, constituted by still smaller-scale molecular interactions; and we ourselves form the substrate of larger-scale entities, such as communities and ecosystems. At that level, the dialogue of which this book is a minute part may constitute the thoughts of a “global brain,” expressed in a vast language we humans can only imagine by analogy with human languages. But its context is beyond our comprehension. Is there a being for whom “