Why do we engage in the kind of inquiry represented by Turning Signs? Thomas Metzinger’s Being No One offers this answer:

At least in principle, one can wake up from one’s biological history. One can grow up, define one’s own goals, and become autonomous. And one can start talking back to Mother Nature, elevating her self-conversation to a new level.

— Metzinger (2003, 634)

Your autonomy, your self-control, raises the level of nature’s self-conversation, which is our conversation with nature. ‘Successful research,’ according to Peirce (W6:386), ‘is conversation with nature; the macrocosmic reason, the equally occult microcosmic law, must act together or alternately, till the mind is in tune with nature.’ The ‘occult microcosmic law’ is your internal guidance system.

It was Prigogine who used the phrase ‘dialogue with nature’ in a book title, but the basic idea was already common. Karl Popper, for instance, describes both perception and scientific method in terms of a question-and-answer process:

… our senses can serve us (as Kant himself saw) only with yes-and-no answers to our own questions; questions that we conceive, and ask, a priori; and questions that sometimes are very elaborate. Moreover, even the yes-and-no answers of the senses have to be interpreted by us—interpreted in the light of our a priori preconceived ideas. And, of course, they are often misinterpreted.

— Popper (1990, 47)

In developing his model of science as ‘enlightened common sense,’ as the formal and public equivalent of the perceptual process common to all organisms, Popper believed he had ‘refuted classical empiricism—the bucket theory of the mind that says that we obtain knowledge just by opening our eyes and letting the sense-given or god-given “data” stream into a brain that will digest them’ (Popper 1990, 49-50). He also points out that Kant had already described the dialogue with nature in his preface to the second edition of the Critique of Pure Reason: ‘our reason can understand only what it creates according to its own design … we must compel Nature to answer our questions, rather than cling to Nature’s apron strings and allow her to guide us’ (Popper 1968/89, 256).

Merleau-Ponty (1945, especially 370-374) presents perception as a dialogue between body and world—a reciprocal relationship of question and answer:

The passing of sensory givens before our eyes and under our hands is, as it were, a language which teaches itself, and in which the meaning is secreted by the very structure of the signs, and this is why it can literally be said that our senses question things and that things reply to them.

— Merleau-Ponty (1945, 372)

The relations between things or aspects of things having always our body as their vehicle, the whole of nature is the setting of our own life, or our interlocutor in a sort of dialogue … every perception is a communication or a communion, the taking up or completion by us of some extraneous intention or, on the other hand, the complete expression outside ourselves of our perceptual powers and a coition, so to speak, of our body with things. The fact that this may not have been realized earlier is explained by the fact that any coming to awareness of the perceptual world was hampered by the prejudices arising from objective thinking.

— Merleau-Ponty (1945, 373)

What Merleau-Ponty means here by ‘objective thinking’ is part of the ‘natural attitude’ arising from the unexamined assumption of a dyadic relation between words and things to which they refer. This kind of ‘objective thinking’ cuts the body out of the semiotic loop by taking at face value the perceived externality of objects, ignoring the body’s involvement in all perception. Semiotic objectivity, on the other hand, always implies a triadic relation among sign, object and interpretant. It also involves three modes or grades of meaning, as Peirce pointed out in the first of his 1903 Lowell Lectures:

A little book by Victoria Lady Welby has lately appeared entitled What is Meaning? The book has sundry merits, among them that of showing that there are three modes of meaning. But the best feature of it is that it presses home the question “What is meaning?” A word has meaning for us in so far as we are able to make use of it in communicating our knowledge to others and in getting at the knowledge that those others seek to communicate to us. That is the lowest grade of meaning. The meaning of a word is more fully the sum total of all the conditional predictions which the person who uses it intends to make himself responsible for or intends to deny. That conscious or quasiconscious intention in using the word is the second grade of meaning. But besides the consequences to which the person who accepts a word knowingly commits himself, there is a vast ocean of unforeseen consequences which the acceptance of the word is destined to bring about, not merely consequences of knowing but perhaps revolutions of society. One cannot tell what power there may be in a word or a phrase to change the face of the world; and the sum of those consequences makes up the third grade of meaning.

EP2:255-6

Each ‘grade’ here involves the lower grades. At the second grade, the interpreter or reader of the word is always dealing with a double context and a double meaning: There’s the context in which the author intended his meaning, and there’s the context of the implicit question for which the reader seeks an answer in this text. Even at the first grade, which assumes a common language, the reader has her default meaning for any given word or phrase, and has to take the context supplied by the author into account in order to guess whether (or how much) that default is relevant to the present occasion of reading this text.

For instance, the word ‘objective’ itself refers in Merleau-Ponty’s text to the assumption that the objects of perception are the sole (or dominant) contributors to the experience of perception; ‘objective thinking’ then is a denial of the ‘communication or communion’ that constitutes perception. But if the reader is, say, a Buddhist thinker, then he might habitually use the word ‘objective’ in a very different sense; ‘objectivity’ might point to the absence of attachment or aversion toward phenomena, in which case ‘objective thinking’ is precisely the kind of thinking from which prejudices do not arise. ‘Objectivity’ for a Buddhist could be a word for the practice of interbeing.

In addition to hidden differences of meaning, the careful reader will be aware of the hidden connections working behind words. Merleau-Ponty refers above to the ‘coition, so to speak, of our body with things’. The phrase ‘so to speak’ marks this as a metaphor, but there’s more here than superficial wordplay: in English the idea of coition is linked to verbal as well as sexual ‘communication’ because we can use intercourse as a synonym for either one. The link between communication and communion is even more obvious. Nor is this merely a quirk of English: And Adam knew his wife … the link between knowing and coition in the English of the King James Bible is a faithful translation of the same link implicit in the Hebrew (Scholem 1946, 235). All of this meaning is going on behind the scenes of the text all the time, provided that the reader negotiates the text with care (with compassion, feeling-together, communion, ….. ). Negotiation too is another word for dialogue …

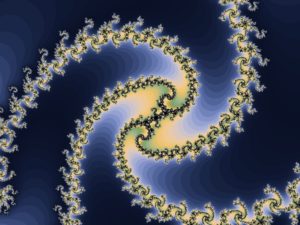

The results of a simple algorithm, though regular and predictable if taken one at a time, can take on great complexity if the algorithm is many times reiterated with the result of each iteration becoming a factor in the next. A classic example of such a nonlinear process is the Mandelbrot set, which can produce an infinite variety of ‘fractal’ images, all generated by a relatively simple formula run recursively on an ordinary computer.

The results of a simple algorithm, though regular and predictable if taken one at a time, can take on great complexity if the algorithm is many times reiterated with the result of each iteration becoming a factor in the next. A classic example of such a nonlinear process is the Mandelbrot set, which can produce an infinite variety of ‘fractal’ images, all generated by a relatively simple formula run recursively on an ordinary computer.