The universe is wider than our views of it.

Category: Objecting and Realizing

rePatch ·12

On observing

Some aspects of Buddhism are more scientific than religious. Consider this verse from the Blue Cliff Record, Case 39:

If you want to know the meaning of buddha-nature, you should observe times and seasons, causes and conditions.

It is essential to your practice of observation that you be aware of its limitations. As Dogen put it in his ‘Genjokoan’:

Though there are many features in the dusty world and the world beyond conditions, you see and understand only what your eye of practice can reach.

According to the glossary of this translation (Tanahashi 2010), ‘beyond conditions’ is ‘格 外 [kakugai], literally, outside frameworks.’ A psychologist might say “beyond conditioning”; in Turning Signs we may say beyond the cognitive bubble. Or we might say that Dogen’s point is the flip side of Peircean pragmatism.

Connext

Everything is connected, but some things are more connected than others.

— Herbert Simon (Pattee 1973, 23)

Dreams and schemes

Every pebble dreams of itself

Every leaf has a scheme— Leonard Cohen (Stranger Music, 399)

My schemes into obeyance for

This time has had to fall— Finnegans Wake, 73

Surdity

Let us swop hats and excheck a few strong verbs weak oach eather yapyazzard abast the blooty creeks.

— FW 16

Thus begins the conversation between Mutt and Jute in the early pages of Finnegans Wake. It continues rather like a dialogue of the deaf:

Jute.— Yutah!

Mutt.— Mukk’s pleasurad.

Jute.— Are you jeff?

Mutt.— Somehards.

Jute.— But you are not jeffmute?

Mutt.— Noho. Only an utterer.

Jute.— Whoa? Whoat is the mutter with you?

Mutt.— I became a stun a stummer.

Jute.— What a hauhauhauhaudibble thing, to be cause! How, Mutt?

Mutt.— Aput the buttle, surd.

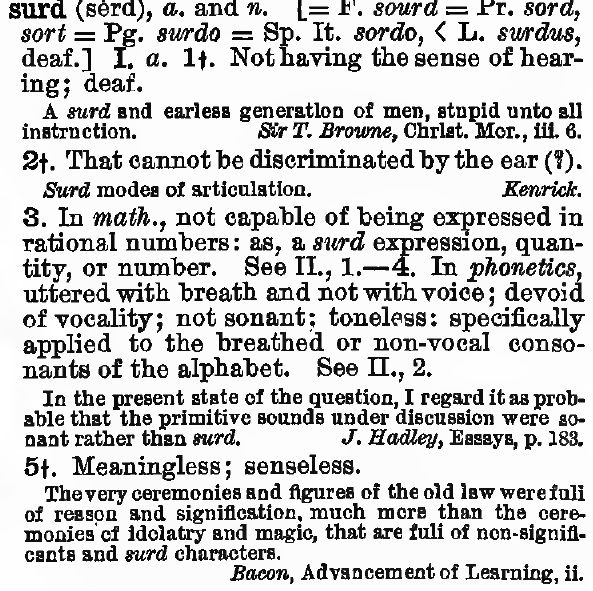

That last word is not often heard in everyday English, but it suits the story here, as the primal meaning of its Latin root surdus is “deaf.” But then the notion of “hard of hearing” slips over (by way of stuttering, stammering and muttering) into “hard to hear,” and thence to “unintelligible” or “irrational,” and thence to “meaningless.” This diversity was documented by C.S. Peirce in the Century Dictionary:

In his later work on logic as ‘the Basis of Pragmatism,’ Peirce used the word as a technical term applied to ‘the relation implied in duality,’ which ‘is essentially and purely a dyadic relation’ (EP2:382). A surd relation is the opposite of a dicible one. In less Latinate diction, you could say that a surd relation is “unsayable,” or perhaps “unreasonable.” It can be experienced but not really described.

For the only kind of relation which could be veritably described to a person who had no experience of it is a relation of reason. A relation of reason is not purely dyadic: it is a relation through a sign: that is why it is dicible. Consequently the relation involved in duality is not dicible, but surd …

EP2:382-3

Since all reasoning is in signs, a ‘relation of reason’ is triadic even if it seems to have only two correlates, two ‘subjects’ (like Mutt and Jute). It lacks the surdity of a ‘purely dyadic relation.’ But the only way our two ‘jeffmutes’ could enter into a purely dyadic relation would be to collide with each other, perhaps in a head-butting battle. The duality of their duel is clear enough ‘aput the buttle,’ but they do manage to swop hats and excheck a few verbs, thus making their relationship more triadic. If they both sound a bit “stunned,” maybe that’s just the effect of taking turns at the bottle.

Turning to genuine triadic relations, and thus to signs, we find that the Secondness of the dynamic relation between Sign and Object – or in communication, the duality between Utterer and Interpreter – must also be genuine, must be a ‘real’ relation, not a ‘relation of reason.’ As explained elsewhere, the element of Secondness or surdity must be involved in any honest attempt to understand, speak or hear the truth.

This may sound unsound or even absurd, but it is borne out by the twisted history of words themselves. If our language were entirely rational, for instance, the word absurd would mean “far from surd,” just as abnormal means “far from normal.” But in fact surd and absurd mean pretty much the same thing. Why? It’s hard to say, surd.

As Peirce remarked in the Century Dictionary, absurd is ‘a word of disputed origin’ – there is no dispute about what it actually means in everyday discourse, but a reasonable account of how it came to mean that has to choose between two possible significations of the prefix ab-. If it means “away from” (as in “absent” or “abnormal”), then combining it with the Latin root surd could not generate the usual meaning of absurd. Some say that the -surd part might come from a Sanskrit root that sounds similar but means “sound” (rather than “deaf”). Then absurd could have meant something like “inharmonious,” and thence “unsound” in the sense of “unreasonable.” The other side in the dispute say that the Latin and English surd is the root, but the prefix ab- acts as an ‘intensive’ rather than a negative (as it seems to do in “aboriginal”), thus making absurdity even more unreasonable or nonsensical than surdity.

The point is that, whether we can explain it or not, the common sense of the word absurd is “contrary to common sense” (CD), because that is how people actually use it. Likewise actual facts, no matter how well known, always carry a residue of unspeakable or inexplicable surdity. ‘Facts don’t do what I want them to,’ as Byrne and Eno put it. The element of Secondness in them keeps our knowledge real and our quest for Truth honest.

Qualities of thought and nature

According to the Peircean theory of cognition, even sense perception is a matter of hypothetical inference. Physiologically, perception is the response of a nervous system, in some specific context, to the arrival of a stimulus to its sensorium, such as a barrage of photons upon the retina. In cognitive terms, ‘each sense is an abstracting mechanism’ (Peirce, EP1:50), and consciously experienced sensations or feelings

are in themselves simple, or more so than the sensations which give rise to them. Accordingly, a sensation is a simple predicate taken in place of a complex predicate; in other words, it fulfills the function of an hypothesis.

EP1:42

Cognition then is a continuous inferential (i.e. semiotic) process whose products range all the way from involuntary perceptual judgments to complex theoretical contructs. These products include sensations and feelings which may be recognized as qualities of the objects perceived or imagined.

Some are inclined to doubt that these qualities have any reality beyond our awareness of them. In the fourth of his 1903 Harvard Lectures, Peirce argued by analogy that ‘qualities of feeling’ – the qualities we recognize in our perceptual judgments, as when we perceive a blue color – are elements of the real universe. They are real because they are beyond our control, i.e. not subject to logical criticism.

the distinction of logical goodness and badness must begin where control of the processes of cognition begins; and any object that antecedes the distinction, if it has to be named either good or bad, must be named good. For since no fault can be found with it, it must be taken at its own valuation. Goodness is a colorless quality, a mere absence of badness. Before our parents had eaten of the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, of course, they were innocent.

EP2:191

There is no way to find fault with a percept, and perceptual judgments are likewise innocent. Any criticism of it ‘would be limited to performing it again and seeing whether with closer attention we get the same result’ – but strictly speaking, it can’t be performed again on the same percept, for as Heraclitus put it, one cannot step twice into the same river. Its flow is the essence of the stream of consciousness.

In short, the Immediate (and therefore in itself unsusceptible of mediation—the Unanalyzable, the Inexplicable, the Unintellectual) runs in a continuous stream through our lives; it is the sum total of consciousness, whose mediation, which is the continuity of it, is brought about by a real effective force behind consciousness.

Thus, we have in thought three elements: first, the representative function which makes it a representation; second, the pure denotative application, or real connection, which brings one thought into relation with another; and third, the material quality, or how it feels, which gives thought its quality.EP1:42

These are essentially the same three elements that Peirce would later call Thirdness, Secondness and Firstness respectively. By 1903, Peirce was ready to affirm the reality of all three: being the elements of thought and reasoning, they are also really elements of any cognizable universe; ‘every scientific explanation of a natural phenomenon is a hypothesis that there is something in nature to which the human reason is analogous’ (EP2:193). The immediacy and spontaneity of Firstness has its part to play in hypothetical models of nature just as forces and regularities do. Therefore, says Peirce,

if you ask me what part Qualities can play in the economy of the universe, I shall reply that the universe is a vast representamen, a great symbol of God’s purpose, working out its conclusions in living realities. Now every symbol must have, organically attached to it, its Indices of Reactions and its Icons of Qualities; and such part as these reactions and these qualities play in an argument, that they of course play in the universe, that Universe being precisely an argument. In the little bit that you or I can make out of this huge demonstration, our perceptual judgments are the premisses for us and these perceptual judgments have icons as their predicates, in which icons Qualities are immediately presented. But what is first for us is not first in nature. The premisses of Nature’s own process are all the independent uncaused elements of facts that go to make up the variety of nature which the necessitarian supposes to have been all in existence from the foundation of the world, but which the Tychist supposes are continually receiving new accretions. These premisses of nature, however, though they are not the perceptual facts that are premisses to us, nevertheless must resemble them in being premisses. We can only imagine what they are by comparing them with the premisses for us. As premisses they must involve Qualities.

Now as to their function in the economy of the Universe,—the Universe as an argument is necessarily a great work of art, a great poem,—for every fine argument is a poem and a symphony,—just as every true poem is a sound argument. But let us compare it rather with a painting,—with an impressionist seashore piece,—then every Quality in a Premiss is one of the elementary colored particles of the Painting; they are all meant to go together to make up the intended Quality that belongs to the whole as whole. That total effect is beyond our ken; but we can appreciate in some measure the resultant Quality of parts of the whole,—which Qualities result from the combinations of elementary Qualities that belong to the premisses.EP2:193-4

So although ‘what is first for us is not first in nature,’ the ‘Immediate’ and ‘Inexplicable’ which ‘runs in a continuous stream through our lives’ shares a Firstness with ‘the independent uncaused elements of facts that go to make up the variety of nature.’

Really?

Perhaps reality is just the illusion that no one will ever see through, despite our most honest efforts.

God, O Arjuna, dwells in the heart of every being and to His delusive mystery whirls them all, as the clay on the potter’s wheel.

— Bhagavad-Gita 18:61 (Gandhi 1926, 233)

Really

Reality is what cannot be imaginary, but can inform your imagination like nothing else.

Whatever you have done, said, thought, deeply heard or read, has contributed something to the situation you are now living in. And then there’s reality, which breaks into your house of habits like a thief in the night.

Eyebeams

Matthew 7:3 asks, ‘why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye?’ (KJV). Good question, says the Dhammapada:

It is easy to see the fault of others, hard to see one’s own. One sifts the faults of others like chaff, but covers up one’s own, as a crafty cheater covers up a losing throw.

In one who watches out for the faults of others, always ready to blame, compulsions increase; such a one is far from extinction of compulsion.— Dhammapada 18:18-19 (Cleary 1994, 58)

We have seen in Chapter 6 the parallel in the Gospel of Thomas, Logion 26. Also very similar to Matthew 7:3-5 is Luke 6:41-2: ‘cast out first the beam out of thine own eye, and then shalt thou see clearly to pull out the mote that is in thy brother’s eye.’ All of these texts (including the Greek version of Thomas, P. Oxy. 1) use διαβλέψεις (‘you will see clearly’). The word used for ‘beam,’ δοκὸν, refers to the bar of a gate or door – something solid and hard to break.

The English beam originally referred more broadly to a tree or post; use of the word in reference to a living, growing tree later dropped out of the language, and now it generally refers to a heavy timber used in construction, or a steel I-beam (named after the shape of its cross section, not after the first-person pronoun). We usually picture the biblical ‘beam in the eye’ as something like a log, in contrast to the ‘mote’ in another’s eye. But there’s another kind of eye-beam.

In a development called ‘remarkable’ by the OED, the original English sense was transferred to a sunbeam (such as the ray of light visible in the distance when it breaks through heavy clouds), and thus to any beam of light. Sometimes this light beam was turned outside in, as it were, referring to a beam that comes through one’s eye from the internal rather than the external world – a metaphor for one’s power of attention. A further metaphorical shift produced a verb for shedding light upon the world by one’s expression, i.e. beaming. Emerson, in his essay ‘Friendship’, used the term ‘eye-beams’ in this social context.

How many we see in the street, or sit with in church, whom, though silently, we warmly rejoice to be with! Read the language of these wandering eye-beams. The heart knoweth.

Emerson also brought an eyebeam into his poem on ‘The Sphinx’ (first published in 1841). C.S. Peirce was fond of quoting lines from this poem in a variety of contexts. Here’s an example from one of his manuscripts on phaneroscopy:

… although the entire consciousness at any one instant is nothing but a feeling, yet psychology can teach us nothing of the nature of feeling, nor can we gain knowledge of any feeling by introspection, the feeling being completely veiled from introspection, for the very reason that it is our immediate consciousness. Possibly this curious truth was what Emerson was trying to grasp — but if so, pretty unsuccessfully — when he wrote the lines,

The old Sphinx bit her thick lip —

Said, “Who taught thee me to name?

I am thy spirit, yoke-fellow,

Of thine eye I am eyebeam.

Thou art the unanswered question;

Couldst see thy proper eye,

Always it asketh, asketh;

And each answer is a lie.”But whatever he may have meant, it is plain enough that all that is immediately present to a man is what is in his mind in the present instant. His whole life is in the present. But when he asks what is the content of the present instant, his question always comes too late. The present has gone by, and what remains of it is greatly metamorphosed.

— CP 1.310 (1906)

The point here is that our immediate awareness cannot be an object of our immediate awareness. But Peirce was already quoting Emerson’s poem to make this point 40 years earlier, in his Lowell Lectures of 1866. He incorporated the eyebeam into his argument that a person is a sign, because he means something, yet is unaware of his own meaning. Like a symbol, he both denotes and connotes, i.e. has both breadth and depth (see Chapter 10):

A man denotes whatever is the object of his attention at the moment; he connotes whatever he knows or feels of this object, and is the incarnation of this form or intelligible species; his interpretant is the future memory of this cognition, his future self, or another person he addresses, or a sentence he writes, or a child he gets. In what does the identity of man consist and where is the seat of the soul? It seems to me that these questions usually receive a very narrow answer. Why, we used to read that the soul resides in a little organ of the brain no bigger than a pin’s head. Most anthropologists now more rationally say that the soul is either spread over the whole body or is all in all and all in every part. But are we shut up in a box of flesh and blood? When I communicate my thought and my sentiments to a friend with whom I am in full sympathy, so that my feelings pass into him and I am conscious of what he feels, do I not live in his brain as well as in my own—most literally? True, my animal life is not there; but my soul, my feeling, thought, attention are. If this be not so, a man is not a word, it is true, but is something much poorer. There is a miserable material and barbarian notion according to which a man cannot be in two places at once; as though he were a thing! A word may be in several places at once, six six, because its essence is spiritual; and I believe that a man is no whit inferior to the word in this respect. Each man has an identity which far transcends the mere animal;—an essence, a meaning subtile as it may be. He cannot know his own essential significance; of his eye it is eyebeam. But that he truly has this outreaching identity—such as a word has—is the true and exact expression of the fact of sympathy, fellow feeling—together with all unselfish interests,—and all that makes us feel that he has an absolute worth.

W1:498

The eyebeam also recurs in Peirce’s later works on logic, in connection with the ineffability of immediate consciousness and the inaccuracy of introspection:

… we shall have to assume that, practically speaking, there is a flow of ideas through the mind, that is, of objects, of which we have the barest glimpse while they are with us, but which are reported by memory after they have been associated together and considerably transformed; and this report, though not very accurate, is substantially acceptable as correct.

… The point to remember is, that whatever we say of ideas as they are in consciousness is said of something unknowable in its immediacy. The only thought that is really present to us is a thought we can neither think about nor talk about. “Of thine eye I am eyebeam,” says the Sphinx. We have no reason to deny the dicta of introspection; but we have to remember that they are all results of association, are all theoretical, bits of instinctive psychology. We accept them, but not as literally true; only as expressive of the impression which has naturally been made upon our understandings.

CP 7.424-5, c.1893

When we do think or talk about thoughts, we are forced to use symbols, perhaps recognizing that symbols grow by being “repurposed,” but blissfully unaware of the repurposing we are doing at the very moment when we take them to simply mean what they mean. And likewise, Peirce observes that logicians, who profess to be experts on forms and methods of reasoning, have for ages neglected the most important and commonly used forms of it.

But it should surprise nobody that the most characteristic form of demonstrative reasoning of those ages is left unnoticed in their logical treatises. The best of such works, at all epochs, though they reflect in some measure contemporary modes of thought, have always been considerably behind their times. For the methods of thinking that are living activities in men are not objects of reflective consciousness. They baffle the student, because they are a part of himself.

“Of thine eye I am eye-beam,”

says Emerson’s sphynx. The methods of thinking men consciously admire are different from, and often, in some respects, inferior to those they actually employ.…

One has to confess that writers of logic-books have been, themselves, with rare exceptions, but shambling reasoners. How wilt thou say to thy brother, Let me pull out the mote out of thine eye; and behold, a beam is in thine own eye? I fear it has to be said of philosophers at large, both small and great, that their reasoning is so loose and fallacious, that the like in mathematics, in political economy, or in physical science, would be received in derision or simple scorn.

— CP 3.404-5 (1892)

This brings us round again to the eyebeams of the Gospels, Peirce applying the ethical message to his fellow philosophers. We are all attending to all sorts of objects, but never to our own attention. We are all signs, but we never know what we mean at the moment of meaning.

Scientific realism

Science, as the most formal and elaborate development of objectivity, is the most focused expression of the realist faith. To play her role as observer, the scientist must assume that the observed domain is a single world ruled by universal ‘laws’ operating independently of all observers. In order to contribute to the consensus on what those ‘laws’ really are, then, she must do what she can to eliminate idiosyncrasies from her own observations.

The striving for objectivity is thus understood, phenomenologically, as a striving to achieve greater consensus, greater agreement or consonance among a plurality of subjects, rather than as an attempt to avoid subjectivity altogether.

— David Abram (1996, 38)

Scientific inquiry aims at a consensus constrained by experiment: we test a hypothesis by drawing predictions from it, i.e. deducing what would happen in a specified situation if it were true, then observing what actually happens in that situation. If the experiment is well designed and produces an observation contrary to the prediction, the hypothesis is refuted or ‘falsified’; a positive result, though not conclusive, tends to confirm the hypothesis.

The failures as well as the successes of the predictions must be honestly noted. The whole proceeding must be fair and unbiased.

Some persons fancy that bias and counter-bias are favorable to the extraction of truth—that hot and partisan debate is the way to investigate. This is the theory of our atrocious legal procedure. But Logic puts its heel upon this suggestion. It irrefragably demonstrates that knowledge can only be furthered by the real desire for it, and that the methods of obstinacy, of authority, and every mode of trying to reach a foregone conclusion, are absolutely of no value.Peirce, W3:331 (1878)

This in a nutshell is the objectivity proper to science – that is, to all honest argument. It amounts to respecting the reality of the object observed rather than clinging to the observer’s or experimenter’s bias. In other words, it relies crucially on inductive logic.

It is of the essence of induction that the consequence of the theory should be drawn first in regard to the unknown, or virtually unknown, result of experiment; and that this should virtually be only ascertained afterward. For if we look over the phenomena to find agreements with the theory, it is a mere question of ingenuity and industry how many we shall find.

Peirce, BD ‘Reasoning’