To begin with, the world of awareness includes only a small part of the physical environment. Furthermore, the world of awareness is organized differently than the physical environment is organized in its own being apart from the organism. The selectivity and species-specific network of relations according to which an organism becomes aware of its environment is called an Umwelt. “Umwelt” therefore is a technical expression meaning precisely objective world. In the objective world of a moth, bats are something to be avoided. In the objective world of a bat, moths are something to be sought. For bats like to eat moths, while moths, like most animals, are aversive to being eaten.

Each type of cognitive organism, we may say, has, so to speak, its own “psychology”, its own way of “seeing the world”, while the world itself, the physical environment, is something more than what is seen, and has a rather different organization than the organization it acquires in the “seeing”. The world as known or “seen” is an objective world, species-specific in every case. That is what “objective” throughout this work principally means: to exist as known. Things in the environment may or may not exist as known. When they are cognized or known, they are objects as well as things. But, as things, they exist regardless of being known. Furthermore, not every object is a thing. A hungry organism will go in search of an object which it can eat, to wit, an object which is also a thing. But if it fails to encounter such an object for a long enough time, the organism will die of starvation. An organism may also be mistaken in what it perceives as an object, which is why camouflage is so often used in the biological world. So, not only is it the case that objects and things are distinct in principle, the former by necessarily having, the latter by being independent of, a relation to some knower; it is also the case that not all objects are things and not all things are objects.

The “psychology” or interior states, both cognitive and affective, on the basis of which the individual organism relates to its physical surroundings or environment in constituting its particular objective world or Umwelt is called an Innenwelt. The lnnenwelt is a kind of cognitive map on the basis of which the organism orients itself to its surroundings. The Innenwelt, therefore, is “subjective” in just the way that all physical features of things are subjective: it belongs to and exists within some distinct entity within the world of physical things. The Innenwelt is part of what identifies this or that organism as distinct within its environment and species. But that is not the whole or even the main story of the Innenwelt. The subjective psychological states … constitute the Innenwelt … insofar as they give rise to relationships which link that individual subject with what is other than itself, in particular its objectified physical surroundings.

These relationships, founded on, arising or provenating from psychological states as subjective states, are not themselves subjective. If they were, they would not be relationships. If they were, they would not be links between individual and environment …. They exist between the individual and whatever the individual is aware of.

The relationships, in short, are over and above the psychological states. The relationships depend upon the subjective states; they do not exist apart from the individual. But they do not exist in thc individual either. They exist between the individual and whatever the individual is aware of …

A concrete illustration should help make the point. The first time you visit a new city, you are easily lost. You have little or no idea of “where you are”. Gradually, by observing various points of reference, the surroundings take on a certain familiarity. What started out as objects gradually turn into signs thanks to which you “know where you are”. Soon enough, you are able to find your way around the new place “without even thinking about it”. What you have done is to construct an lnnenwelt which organizes the relevant physical surroundings into a familiar Umwelt.

— Deely 2001, 6-7

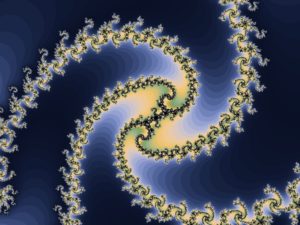

The results of a simple algorithm, though regular and predictable if taken one at a time, can take on great complexity if the algorithm is many times reiterated with the result of each iteration becoming a factor in the next. A classic example of such a nonlinear process is the Mandelbrot set, which can produce an infinite variety of ‘fractal’ images, all generated by a relatively simple formula run recursively on an ordinary computer.

The results of a simple algorithm, though regular and predictable if taken one at a time, can take on great complexity if the algorithm is many times reiterated with the result of each iteration becoming a factor in the next. A classic example of such a nonlinear process is the Mandelbrot set, which can produce an infinite variety of ‘fractal’ images, all generated by a relatively simple formula run recursively on an ordinary computer.