The wise is one alone, unwilling and willing to be spoken of by the name of Zeus.

— Heraclitus (Kahn)

Is the Creator unwilling or willing to be called by the name of God?

The wise is one alone, unwilling and willing to be spoken of by the name of Zeus.

— Heraclitus (Kahn)

Is the Creator unwilling or willing to be called by the name of God?

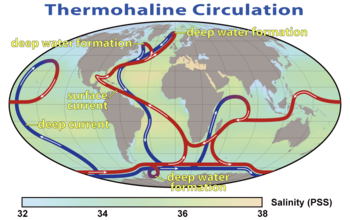

The ancient Greeks of Homeric times imagined the earth as a flat surface surrounded by the river Okeanos, the source of all waters – also described, in a few passages, as the source of all the gods, and even of all things (Turning Signs, Chapter 10.) “Okeanos” was not only a precursor of the meaning cycle but also of current models of the circulation of water in the planet Earth’s oceans.

now appearing under your nose and between your eyes:

We’re all found of our anmal matter.

— Finnegans Wake 294, footnote

One hour’s reflection is preferable to seventy years of pious worship.

— Islamic hadith as quoted by Bahá’u’lláh (Kitáb-i-Íqán)

Zhuangzi and Hui Shi were strolling across the bridge over the Hao river.

Zhuangzi observed, “The minnows swim out and about as they please—this is the way they enjoy themselves.”

Huizi replied, “You are not a fish—how do you know what they enjoy?”

Zhuangzi returned, “You are not me—how do you know that I don’t know what is enjoyable for the fish?”

Huizi said, “I am not you, so I certainly don’t know what you know; but it follows that, since you are certainly not the fish, you don’t know what is enjoyment for the fish either.”

Zhuangzi said, “Let’s get back to your basic question. When you asked ‘From where do you know what the fish enjoy?’ you already knew that I know what the fish enjoy, or you wouldn’t have asked me. I know it from here above the Hao river.”— Zhuangzi 45.17.87–91, tr. Roger Ames (Dao De Jing: A Philosophical Translation, 108-109)

Who knows what you know from where you are?

Here on Manitoulin Island, we’re trying out a new kind of gathering which brings a small group of us together for some deep conversation. First we focus on a song, saying or sacred verse, then we hear what it brings forth from each of our hearts.

We call these sessions Creative Words. Readers of Turning Signs can think of a ‘Creative Word’ as a kind of turning symbol. But you don’t need to read the book or know anything about signs and symbols to take part in one of these conversations.

My wife Pam and I host these CW gatherings in our living room (a.k.a. the Honora Bay Free Theatre, where we also host Manitoulin movie nights.) Usually there’s about four to six of us, and when we’re all ready, we prime the conversation with a short text, somewhere between a sentence and a paragraph or a song. It could be something already posted on this blog, but we don’t reveal the source or context until we’ve all had a chance to enter the realm of thought-feeling created by this Creative Word, using some focussing practices to direct our collective attention. Then we explore that realm by engaging in dialogue with one another and with the text. In this way we recreate the world created by the “Word,” and recreate ourselves as well.

A picture may be worth a thousand words of information, but the recreation of a single saying can be worth a million pictures to a mindful heart. We think of CW as an antidote to the information overload that we all tend to suffer in this media-flooded world. Pam and I, as Bahá’ís, also think of it as part of the service we can render to our fellow humans. Bahá’ís sometimes refer to the revelation of Bahá’u’lláh as the “Creative Word,” and one of its precepts is to “consort with the followers of all religions in a spirit of friendliness and fellowship.” Even if you’re allergic to all religions, you’re still welcome at CW sessions! What matters, we think, is “that the peoples and kindreds of the world associate with one another with joy and radiance” (Bahá’u’lláh again).

Our first Creative Words gathering took place on the evening of January 31, 2018, and we intend to hold one every 19 days (that’s once a Bahá’í month). We’ll post reminders on Resilient Manitoulin and the Calendar connected with it. If you want to join us for a session, you’ll need to let us know beforehand, but you don’t need to bring anything other than friendliness and fellowship. For more information (or recreation!) use the “Contact Me” button on my blog, or phone me or Pam. We’ll be happy to hear from you.

To enjoy freedom, we have of course to control ourselves.

In a Zen community, the monk in charge of cooking for the other monks is called the tenzo. Zen master Dogen, in his youth, learned some very important lessons from the tenzo of one community. Later he incorporated those lessons into a manual written as guidance for his own community. Here are two translations of a short passage from Dogen’s Tenzokyokun (Instructions for the Tenzo):

If you cannot even know what categories you fall into, how can you know about others? If you judge others from your own limited point of view, how can you avoid being mistaken? Although the seniors and those who come after differ in appearance, all members of the community are equal. Furthermore, those who had shortcomings yesterday can act correctly today. Who can know what is sacred and what is ordinary?

— Tanahashi 1985, 62

Even the self does not know where the self will settle down; how could others determine where others will settle down? How could it not be a mistake to find others’ faults with our own faults? Although there is a difference between the senior and the junior and the wise and the stupid, as members of the sangha they are the same. Moreover, the wrong in the past may be right in the present, so who could distinguish the sage from the common person?

— Leighton and Okumura 1996, 45

Charles Peirce would regard these as two interpretants of one sign. As he remarked of a proverb, ‘Every time this is written or spoken in English, Greek, or any other language, and every time it is thought of, it is one and the same representamen’ (EP2:203). In Peircean texts like this one, ‘representamen’ and ‘sign’ are two words for the same thing – which is obviously not an existing physical “thing,” since it can be embodied many times in many ways. But each translation, each embodiment, is also a sign in its own right; for ‘every representamen must be capable of contributing to the determination of a representamen different from itself’ (Peirce, same paragraph).

Each person who actually follows Dogen’s guidance has to translate it into a functional part of his or her own habit-system, an interpretant sign which will in turn determine actual behavior. That interpretant behavior may contribute to the guidance systems of other monks … and so on. If that happens, the monk’s potential to be a sign is realized. All of this is part of what it means for Dogen’s expressed thought to mean anything. And part of what it means for you to read the two translations above is to read them as interpretants of one sign even though they are two signs. Try that …

You always find what you’re looking for in the last place you look.